Connectivity Builds Independence In Afghanistan

|

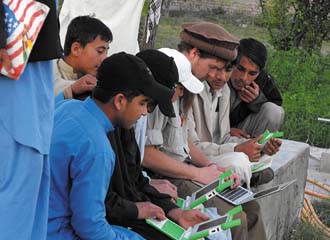

Children in the Jalalabad area of Afghanistan surround Todd Huffman, |

The road to stability in Afghanistan is being paved with telecommunications systems. Through the strategic use of technology, the country already is experiencing improvements in connectivity that will continue to progress until the governance, industrial and the socio-economic state of the country all reap the benefits. If plans, activities and cooperation continue as they have for the past few months, Afghanistan will be poised by the middle of this decade to take its place among the most economically stable and technologically savvy countries in the world.

The International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) Telecom Advisory Team (TAT) is leading the work in partnership with the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, in particular its Ministry of Communications and Information Technology (MCIT). The core team comprises less than 10 members from the U.S. Defense Department and private industry. It has put into place a methodical approach to introducing technology as a viable means not only to stabilize the country but also to help it thrive.

Work began on July 1, 2010, with TAT’s long-term strategic vision and road map illuminating the steps necessary in the first 100 days to set conditions for success. Subsequent 100-day relooks are being conducted to shape the focus of the work to ensure the team addresses the continuously changing needs of a dynamic operational environment. The strategy lines up with the MCIT’s goals.

Larry Klooster, TAT’s senior technical adviser, who works for the Defense Information Systems Agency, explains that during the first hundred days of this project—July 1 to mid-October 2010—the team assessed the existing state of telecommunications systems and refined its strategies for the way ahead. It also developed strategic partnerships to grow the local information and communications technology (ICT) industry and increase telecommunications capacity for the Afghan government. If NATO wants to move the military out of the area, it needs to help the government stand up and ensure the economy is stable. This means creating legitimate businesses that create jobs and helping provide services such as education and health care to the citizens, he says.

Klooster emphasizes that the MCIT and Afghan government are TAT’s primary clients. The government creates the policy, which is handed to the MCIT. The ministry then develops its own strategy and shares it with TAT. “As a result, we know the strategies across organizations and programs to support government agencies, nongovernmental organizations and international organizations such as the World Bank, which has made investments in the ICT programs,” he explains.

TAT’s motto has been Afghanistan first, which means the team looks first at Afghan companies with programs that could be developed further. Its goal is to synchronize and harmonize the programs sponsored by the embassy, various elements of the economic sector and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to deconflict or leverage similar programs.

To accomplish its mission, the team decided it had to determine the MCIT’s objectives. Initial steps included developing relationships with personnel in the MCIT, U.S. State Department, Defense Department and the USAID. Within the first two weeks, Afghan government officials came to believe this team would not be a typical Defense Department program that would attempt to take charge. Instead, they understood that this would be a collaborative effort because TAT’s strategy document emphasizes the team’s goal: to assist the Afghan government to accelerate the benefits of ICT as an essential service enabler, Klooster relates.

The telecommunications industry was a likely candidate as a means to stabilize the country because during the past five years, the Afghan ICT sector has been the most successful legitimate economic sector in the country. With an annualized growth rate of more than 77 percent over the past few years, the sector provides 19 percent of the country’s tax revenues, and its services are available to more than 80 percent of the population. Cell phone penetration exceeds 50 percent.

The TAT document that describes plans for the future includes four goals. Work on the Optical Fiber Cable Backbone Ring Network, which encircles the outer rim of the country and in some places extends into bordering countries, began in April 2007. The first goal was to establish a plan to complete the terrestrial ICT broadband network backbone made primarily of fiber. The MCIT came to the ambassador at the end of July 2010 to ask for funding not only to complete the fiber backbone but also to back it up using a microwave string around the backbone ring network.

Over the next weeks, the team brought people together and identified the true situational awareness of the network ring. It determined which portions of the ring needed repair and where the gaps and redundancies existed. As a result of this assessment and planning, all major Afghan cities will be connected by June 2011, and by December 2012 connectivity with redundancy is scheduled to be in place. The Afghan government is providing the bulk of the funding through the MCIT, with additional financial assistance from the U.S. government and the World Bank.

The team currently is focused on opportunities to stimulate public and private-sector ICT development and its use to transform local economies and service delivery. Included in this effort is the extension of ICT services to rural areas to facilitate local population access to social services and to improve quality of life. Challenging these efforts are the ongoing insurgent actions to turn off many cell towers at night, which creates gaps in access to emergency services and reduces cell provider revenue. The team is investigating ways to mitigate this situation and help restore around-the-clock cell service in affected areas. Efforts also are underway to explore options for extending ICT services to rural areas in a high-threat environment. These options include synchronizing implementation with military actions to achieve a safe and secure environment, as well as exploring approaches to ensure needed capacity is available to sustain operations and provide services.

|

TAT member Larry Wentz visits areas around Jalalabad. |

Next, the team went to the MCIT to determine how it could provide additional assistance. As a result, in low- to medium-risk areas, cell companies are subsidized to replace cell towers that insurgents destroy and are provided funding for additional security. Initial security eventually was supplemented by the Afghan local police patrolling tower locations.

In addition, one effort to put around-the-clock cell service into some of the most dangerous rural areas in Afghanistan has begun. The plan is for special forces to go into an area and establish security. Once secure, the residents in the area must agree that they want the service, and a safe area for a tower’s construction must be established before cell service will be provided. Finally, the long-term security of the tower must be ensured.

TAT’s third goal was to support organizations that assist the legitimate government and stability operations by moving outward from the cities into rural areas. By extending government services from provinces to districts to villages, Afghan citizens will begin to trust and support their government, Klooster asserts.

The fourth goal comprises some of the largest matters at hand: socio-economic growth and capacity development, Klooster relates. The team describes the former as the ability to increase telecommunications connectivity into fields such as agriculture, education, finance and health care. In terms of increasing economic growth and connectivity within the nation, the objective is to migrate toward education and training development in the right skill sets, teaching English and computer skills to citizens, and educating government elements in human resources and management skills.

Larry Wentz, a special adviser who came from the National Defense University to work on TAT, explains that capacity growth depends on education and training. “Part of capacity development is looking at how we can use ICT to develop needed skill sets to manage the ministry, regulatory authority and business functions to migrate toward e-government and e-business solutions,” he states.

For example, text messaging could be used to help farmers obtain information about pricing or to support education and health by connecting teachers and health care professionals to new knowledge bases, he says. The younger generation is picking up the technology quickly, so if children and young adults are provided with computers, they not only will improve their own skills but also share them with the country’s elders, just as digital natives are teaching digital immigrants worldwide, he adds.

Trust in the team grew quickly, and it became a one-stop shop for information about the ICT sector because it has situational awareness of the availability of technologies and connectivity—the assessment identified all available programs and their status. “People need cell towers in certain areas and come to ask us if they are in place. We have contacts with major providers of the towers, and we can connect with them to find out,” Wentz says. “We underestimated the value of this document because it lists the strategies, programs and status, which is incredibly valuable.”

The first 100 days were spent on assessments and concepts, and some work was completed. The second 100 days, which began in January, feature the continuation of the work and signify the beginning of the implementation phase. Work on the ICT backbone is ongoing, and the cell coverage development plan was refined. The ECCS did not turn out to be a complete solution. “We thought, ‘We will stand up this network, and they [the cell service providers] will come,’” Klooster shares. It did not quite work out that way, he admits.

So the team came up with an alternative solution that involves law enforcement to ensure that attacks on cell towers are investigated and the offenders pursued. Citizens wanted anonymity of their cell service provider, because once insurgents found out which company they were using, they received calls threatening to destroy those towers. To combat this threat, security and insurance on cell towers has been implemented.

The strategies began solidifying when TAT went to each of the cell companies, explained the plans and gained their trust. As a result of the ECCS, the country’s four cell service competitors began to collaborate to solve mutual problems, Klooster relates. One ECCS contract has been awarded, more may be awarded in the future, and the Afghan National Security Force–Cellular Service has sponsored its first conference for industry.

TAT has figured out ways to obtain additional funding. For example, for the special forces program, the team asked ISAF for $500,000 to demonstrate how this program could work in one location. Instead, the ISAF is considering granting the program $2.5 million because the organization wanted cell towers installed in five locations to determine if the approach would be effective. “This is the first part of the socio-economic growth for rural areas,” Klooster shares.

Another mantra of TAT members is to provide only goods and services that Afghans can sustain after NATO forces leave the country. The current transition plan calls for this to start to occur in 2014. Cell companies that received seed money eventually will generate profits if the strategies for cell tower security continue to be put into place, and this in turn will generate jobs and tax revenue, Klooster says.

Wentz points out that power distribution is one issue that must be addressed by Afghanistan and TAT. Because power sources are not plentiful and reliable, the country will have to look at alternative renewable energy sources such as solar, water and wind. Currently, many cell providers use solar energy, he relates.

Once the results of TAT’s approach are determined, it will be time to move Afghanistan further into the information age, Wentz states. The newest initiative is e-Afghanistan, which exploits new technologies to deliver government services electronically—e-government. This will involve examining how cell service can move to the next-generation of capabilities—from 2G to 3G.

Wentz has been impressed with the initial work the Afghan government has done in the areas of regulations and licensing. Early on, the country’s parliament approved telecommunications laws and regulations, which created the legal basis for telecommunications businesses to operate. Staffing also was approved, so regulators could enforce the laws. This work—including enforcement—will need to continue, he adds.

WEB RESOURCES

Ministry of Communication and Information Technology: www.mcit.gov.af

International Security Assistance Force: www.isaf.nato.int

NATO Training Mission–Afghanistan: www.ntm-a.com

Comments