A Lot of Blood in Kandahar

|

The original hospital at Kandahar Air Field, Afghanistan, consisted of two tents, shown here marked with red crosses in a photo taken from the air traffic control tower. The new brick-and-mortar facility provided by NATO offers far more square footage, as well as the equipment needed for world-class treatment. |

Cmdr. Rick McCarthy, USN, director of administration for the NATO hospital in Kandahar, tells a lot of gory war stories: like the one about the 18-month-old toddler with a bullet wound in one arm. Or the report about the Afghanistan citizen who, following an explosion, had to have rocks picked from his face and lumps of dirt pulled from the tops of his eyeballs. Or the story about the soldier who had his face crushed by the armor-clad body of one of his buddies.

Cmdr. McCarthy tells those stories to illustrate the world-class treatment that coalition forces and Afghan citizens receive at the hospital. “In October, we had a severe trauma from an explosion. We had seven surgeons from three different countries working on one patient at the same time. Two surgeons were working on his head and skull; three more were working on his core; and two were working on his lower extremities. That’s phenomenal,” the commander says.

That treatment is sustained in part by state-of-the-art technologies, including a hospital tactical operations center (TOC) fed by several networks that coordinate medical treatment amidst the chaos of combat. The TOC handles inbound patients. An air medical evacuation (medevac) liaison team handles patients outbound to Landstuhl, Germany, where most trauma patients are moved within 24 hours. The two teams use a variety of communications technologies, including the nonsecure Internet protocol router network; the NATO Secret Network, which is the heart of the Afghan Mission Network; a NATO chat function known as JChat; and more traditional tactical radios.

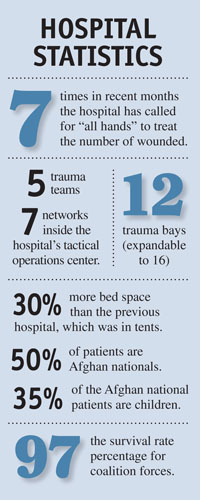

“I think they’ve got roughly seven networks in this one room that covers all the communications modalities they need to cover. That [TOC officer] monitors Mission Secret, which is the classified system, watching JChat—that online chat room—all day long. He’ll notify our trauma teams to let them know what’s inbound. He’ll give them the details of the injuries, if we get that, and he’ll notify the rest of the staff so we can dispatch members to the flight line,” the commander relates.

The hospital classifies injuries as alpha, bravo or charlie. Alphas are the most critical injuries; charlies include minor injuries such as sprained ankles or other routine wounds that can wait 24 hours for treatment; and bravos fall somewhere in between. Usually, the hospital staff will have up to 15 minutes’ notice before medevac helicopters arrive, but that is not always the case. “There are times when we get the word that alphas are inbound now, now, now. The helos are almost on our door, and we’re scrambling to be there when the helos land because we do not want to be the delay factor. We’ve got to be there to get them,” he emphasizes.

|

He credits the hospital’s interventionist radiologists with saving at least nine lives in a matter of months. These doctors insert a variety of instruments through blood vessels to diagnose or treat patients. “If you have vascular injuries—and we’ve had several—where their legs are blown off and the surgeon can’t stop the bleeding, the radiologist will go through the neck, go down from the inside and stop the bleeding, clot it. The surgeons couldn’t get to it, but he could,” the commander says.

One group of soldiers on a dismounted patrol encountered an improvised explosive device, and one soldier, who was wearing body armor, was blown into the soldier behind him. This resulted in a face crushed by the impact of the body armor. “When he was here, his face was swollen. His artery was bleeding out into his face, and he was swelling, but they couldn’t get in to get at it. The interventional radiologist went in through the leg and came up and shut off the bleeding that way. If it weren’t for that capability, he would have bled into his face and died,” Cmdr. McCarthy relates.

The commander also credits field medics for treating wounded soldiers before they ever get to the hospital. “A big part of our ability to maintain a 97 percent survival rate for coalition forces truly is the people in the field—the medics. We had one patient come in here, a triple amputee. When he got here, the tourniquets were all applied. He was wide awake. He was talking to us, telling us what he had for breakfast. He was giving us his name, his background history. His blood pressure was 120 over 80. That’s amazing.”

The hospital also is equipped with a 64-slice computerized axial tomography (CAT) scan machine. Cmdr. McCarthy equates a “slice” with a processor. In U.S. hospitals, 32-slice machines are most common. In U.S. Army field hospitals, 16-slice machines are standard. “It takes more time to load a patient onto the machine than it does to take a scan. Once the patient is on there, we can do a scan head-to-toe in approximately 20 seconds,” he explains. Some patients require a second scan, which includes being injected with iodine so that the second image will present a contrast. In that case, the entire process still can be done in five minutes or less.

The CAT scan is fully digitized, and images are loaded instantly onto a server known as MedWeb, where they are visible to hospitals across the theater via the Joint Theater Medical Network. That ability to share the images is necessary when patients are transferred from one hospital to another. “That network is dedicated to the uploading of those images so that others can see them, and we don’t impact our regular unclassified networks,” Cmdr. McCarthy states.

The system’s bandwidth demands initially sparked some debate, but U.S. military officials argued for its necessity, and the United States provided it to the Joint Theater Medical Network to reduce negative effects on other networks. Although it is a bandwidth hog, the CAT scan provides a view of internal injuries that might otherwise go undiagnosed. “You can imagine the kinetic energy from improvised explosive devices and so forth. Yes, it rips off legs, but all that energy really shakes things up internally—things you just don’t see in your normal life,” the commander says.

In Kandahar, “state of the art” is about more than information technology. It can indicate blast-proof doors or a rocket-resistant roof, both of which are included in the building design. It also can refer to special tables that allow doctors to operate on the front side of a patient, immediately flip the patient over, and work on injuries on the back side. Even clocks throughout the building are synchronized, which is important when precision timing and coordination mean life or death.

The hospital in Kandahar also requires a security staff to pat down patients who may be carrying dangerous items off the battlefield. Shortly after his arrival in theater, Cmdr. McCarthy says, a grenade rolled out of patient’s pocket and landed on the foot of one of the hospital staff members.

The hospital is a German design built by a Turkish contractor and overseen by NATO’s Maintenance and Supply Agency. NATO’s Consultation, Command and Control Agency oversaw much of the equipping of technology, some of which was contributed by the United States.

The treatment in Kandahar is at least as good as the treatment patients could receive in the United States, Cmdr. McCarthy insists. “We will compete with any facility in the United States,” he says. He compares the Kandahar facility to the premier trauma center in Baltimore, where doctors conduct roughly 90 mass transfusions a year that require more than 10 units of blood. “In the months of August, September and October, we averaged over 1,000 units of blood a month. That’s a lot of blood.”

WEB RESOURCES

ISAF NATO Hospital article: http://bit.ly/9sdOtF

Portsmouth Naval Medical Center: www.med.navy.mil/sites/nmcp/Pages/MedHome.aspx

Comments