R&D IN THE INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY - PLENTY TO GO AROUND

The intelligence community (IC) is a $75 billion submarket within the federal complex. This alone is staggering. Being close to Washington DC, we tend to forget just how much money this really is. If this figure were a nation’s gross domestic product (GDP), it would be the 60th largest country in the world and larger than 2/3 of all nations and their respective GDP output (there are currently 181 nations in the world).

This article will first discuss the broader IC funding imperatives, then put this in the context of the FY11 budget as well as some tactics to getting started.

Does the United States intelligence community spend any of its $75B on research, development, science, technology advancement and other core capabilities? You bet!

The current hand wringing over cutbacks should not be too much of a concern for those looking towards the IC. Simply put, the federal government makes noises about economizing but any such budgetary slicing amounts to very little in the broad picture. We tend to track the DoD in these discussions because it is an acknowledged truth that approximately 75% of the intell community eventually flows to the Defense of Department.

Hence, when the SECDEF

Having been in the federal market for about twenty-five years, I tend to define opportunities broadly because for every rule there are many exceptions. First, I believe there are three imperatives to beginning a search for funding if you believe you have an innovation for the intelligence community.

First, don’t limit your innovation to the IC agencies. Think opportunistically and creatively about your unique innovation, and let the professional business developers hunt-down the money that will fund its roll-out. For example, the specific IC mission may have only one application of your technology. However, there is probably a list of other logical targets outside the IC, if your innovation can be reshaped or put into a different form factor. I argue this because intell agencies often take over twelve months to spend money, hence, the civilian government agencies often move faster than the IC agencies and will be able to sustain your R&D while you continue to sell to the IC. Safe to say, there are more nooks and crannies in the federal government market that any one person can know.

Here is an example. If you have a passion for, say, the application of nanotechnology to clothing (pick any topic, the point will still be the same), thinking broadly about its applicability will allow you to develop use cases for several or perhaps many sectors of the federal market. Would the CIA use it differently than the Department of Agriculture? Of course, and the chances are good that if this innovation is useful in one agency, it has applicability in another; you must simply find that applicability vis a vis each agency’s charter. Put differently, most agencies fund research that produces game-changing solutions, however, each agency’s use of a core technology will reflect their unique mission.

Secondly, most solutions tend to be only one increment better than the last solution. Take this to heart and work with it, not against it. Evolutionary gains are usually the order of the day when it comes to getting a program manager’s attention. The reasons why this is true are many, but perhaps the number one reason is this: risk is a bad thing to most federal program managers!

For example, if you could develop a technique that charges remotely located batteries with a wireless trickle of electrons, it may need to be scaled back in order to take advantage of existing and stable broadcast frequencies rather than harvesting a new portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that requires new infrastructure. Especially towards the intelligence community, start with an agency’s core mission and ask questions like, “what incremental innovation will yield an advantage over the enemy or the current approach and with whom should I team to deliver this capability?”. (BTW: this wireless trickle of electronics to charge batteries would in fact be highly useful to most federal agencies but for a wide variety of reasons!) This general point was validated, in my opinion, by Dawn Meyerriecks, Deputy Director of National Intelligence for Acquisition and Technology, recently:

The next step for vendors, she says, is to differentiate [their offering] based upon understanding the Intelligence Community’s mission. “We will continue to pay top dollar for that because that is where the problem is,” says Meyerriecks.

(Government Executive Magazine, June 1st, 2010 by JD Kathuria)

What the IC leadership is looking for are catalysts that produce game changing capabilities. And at high levels organizationally, the leadership understands clearly that these will come in small steps.

A third imperative in funding the development and roll-out of your innovation is the need to focus on acknowledged problems that require immediate solutions. (By trying to solve an unacknowledged problem, you may fall into the category of “missionary” and this can take a long time!) An interesting case study is how Congress and the DoD are funding the defeat of the improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Every mother of a soldier in Iraq or Afghanistan (and even Mumbai) cares about solving this one…and urgently! The collection of technologies that mitigate the effects of IEDs is truly a broad list of sub-problems have threads of their own—everything from innovations in war fighter training to testing of primitive explosives as well as research into airborne SINGINT detection platforms and electronic warfare. Much of the research and development is performed in a classified manner, so it qualifies as “intell community”, by my definition. In fact, this particular goal (defeating IEDs) is so important it has separate Pentagon authority and funding at the three-star level (lieutenant general, in this case). My point is that when properly motivated, the nation can get behind any problem and fund the creation of solutions, but it is incumbent upon the innovator to match his core innovation with a very specific and applied solution. This is usually a larger challenge then the core R&D innovation itself and requires a balance between creativity and dogged focus.

From here, let’s examine the FY11 budgetary landscape. (This data has been gleaned from the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments and its Analysis of the FY11 Defense Budget report by Todd Harrison (http://www.csbaonline.org)).

For starters, beginning with the FY 2011 planning window, the Defense budget will be approximately $712B. The “black” or classified portion of this aggregate will continue to stay healthy from a funding standpoint—at a whopping $57.8 billion. The difference between this figure and the $75B mentioned earlier would be the purely civilian intell budget figures-that do not usually pass through the Pentagon budgets and includes everything from mundane analysis to really cool satellite technologies.

Generally speaking, there are three ways to slice the DoD’s classified budgets: operations and maintenance (O&M), acquisition and research and development (R&D). Classified O&M will realize a real increase of 10 percent over FY10 figures… or about $18B. Classified R&D has risen steadily over the past decade from 19 percent in FY 2000 to 30 percent of total RDT&E funding in the FY 2011 request for a total of about $22B. And classified acquisition and procurement should comprise approximately 15 percent of the total DoD budget or roughly $17B (reflecting about 8.8 percent overall rise in procurement). The bottom line for IC related R&D funding is that there is at least $22B not counting civilian intelligence.

In summary, an innovator must first think broadly and creatively about “what kind of federal and intell problems does a given solution address?” Putting all of one’s eggs in the intell community is dangerous. Secondly, once a short list is developed, a hyper-focus in necessary that directly connects a value proposition of the innovation into an agency’s core mission and delivers incremental gains. The more specific…the better. Finally, only focus on problems that someone truly cares about solving. There needs to be a balance between starting with problems and backing into a solution versus starting with your innovation and searching for a problem. In the current spending environment, monies are certainly available to those who can deliver incremental solutions that meet core mission requirements.

At this point, let’s take a tactical dive, deeper into the agencies.

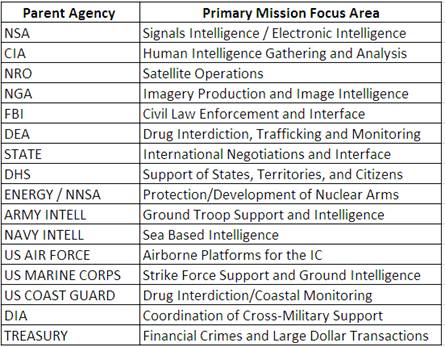

By drilling down into the sixteen agencies that comprise the (generally accepted definition of) the intelligence community, it is not too difficult to notionally develop broad targets. For instance, if your core innovation is camera lens technology, it may make more sense to begin with the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA) rather than the NSA. Alternatively, if you have an innovative algorithm that increases the management of the signal-to-noise ratio in a telecom network, the NSA is the better.

Here is a listing of the core IC mission areas:

Assume that each organization has R&D funding for their respective core mission areas—anything to help them achieve their federal and statutory goals faster, with less risk or less collateral damage. And when they believe you need some help they may choose one of the 316 full-blown laboratories to assist you (see: http://www.federallabs.org/labs/results/).

If you begin your search from the core mission of each agency and ask “what incremental innovation will yield an advantage over the enemy or the current approach and with whom should I team to deliver this capability?” you are on the right track.

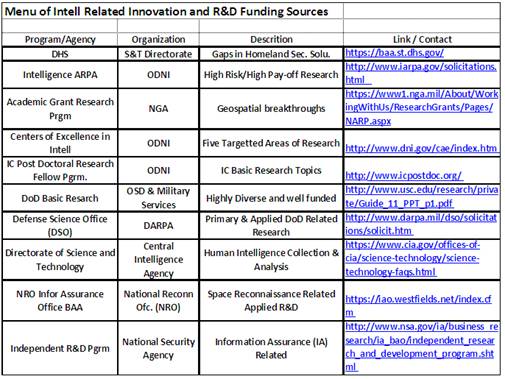

Here is a very partial listing of some targets that make sense, but it is only a beginning.

In most cases, each of these organizations publish broad agency announcements (BAA) and you simply need to watch for them(or predetermine when they’re being released). If you are not seeing the topics that you’re able to address, you are either looking at the wrong agency, or you need to find the right person in that agency and explain to him, the value of your innovation and tie this to their mission. If you’re successful, you may influence future BAAs that request research in that specific area. Also remember, if the agency manager sees something truly unique and desirable, they could fund a cooperative research and development agreement (CRADA). Frankly, the greater challenge is explicitly connecting your unique innovation with a specific part of their mission…as an outsider. You may cry, “how in the world do I know how the NSA wants to use this gadget or gizmo?!?” In my estimation, you must network your way to that knowledge by trusting the right persons. Of course, non disclosure agreements will bind the commercial systems integrators with whom you speak, and the government personnel as well. Until they envision a positive impact or game-changing outcome as a result of your innovation, the details of “how to get you the funding” (i.e., BAA, CRADA, etc.) won’t matter.

In other cases, there are intell community requirements that are expressed via the non-traditional outlets; Special Operations Command (SOCOM) is a good example. From their web site you can learn points of contact and actual innovation requirements. And if you don’t see what you’re looking for, submit your idea via their portal! I can attest to this working in one agency; there is typically a review committee that actually looks over your submission. The better you can articulate a benefit or highly valuable outcome, relative to their mission, the more successful you’ll be. What more could you expect from a combatant command that is considered the “tip of the spear” in our global war on terror?

A top down approach may be more to your liking. At the level of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, they solicit ideas to help our troops and special operations forces. Their chief technology officer (CTO) for innovation and research has authority to direct, spend and manage large portions of resources. Currently this is The Honorable Zachary J. Lemnios, Director, Director, Defense Research & Engineering; his message is fairly straightforward:

The U.S. Department of Defense is looking for a few really good ideas - products, services, prototypes, and concepts that advance our military's missions. Use this new portal to submit your ideas and receive an initial response in less than 30 days. (see: http://www.acq.osd.mil/ddre/)

In summary, there is over $22B spread out among the Defense and civilian intell organizations and agencies; you should assume they are looking for innovative ways to spend this money and your goal is two-fold: get to the most logical targets and clearly articulate the specific value of your innovation relative to each agency’s unique charter. And have some fun along the way!

Reference

SOCOM, http://www.socom.mil/sordac/Documents/BusinessOpportunitiesWithUSSOCOM.pdf

Comments