Technologies Creating Brave New Connected World, But At What Cost?

Is the emergence of robotics raising a generation of meat puppets? Are you a meat puppet?

While the questions posed by Bob Gourley, co-founder of Cognitio, drew a little laughter from attendees at the AFCEA International/George Mason University Critical Issues in C4I Symposium, they should provide serious fodder for discussion on the people whose jobs are about to be replaced by robots.

“I hope you laughed at that the term, but I hope that that makes it memorable for you,” Gourley said of slang adopted from sci-fi novels. “I hope it leads to a serious thought … about the people whose jobs are being displaced, because it’s going to be in the millions.”

The nation is developing robotic cars, robotic ships and robotic solutions to replace coal miners and truck drivers, he shared.

Gourley presented his coined term “cambric” to illustrate the seven technologies that, when put together, will disrupt humanity, he said at the symposium, held May 18 and 19. Cambric stands for cloud computing, artificial intelligence, mobility, big data, robotics, the Internet of Things and cybersecurity.

The trends hold great potential for a “great world” if well-engineered and administered, from improved healthcare to law enforcement and military. “But, we have to be realistic too,” Gourley said. “There are serious risks in all this stuff that requires us to pause and think. Are we going to live in a world with increased risk to privacy? Are we going to make it easier for white collar criminals … to steal financial information? What about job displacement? We owe it to all ourselves to have that discussion.”

Leading the trend is the pervasiveness of the supercomputers that are today’s smartphones. Roughly 70 percent of U.S. consumers have one. “We’ve gone through a threshold now that is irreversible,” Gourley said. Smartphones offer the ultimate biometric asset. “Where this thing has been is where you are. It really does say who you are, where you’ve been and what you’ve been doing.”

The emergence of virtual reality and augmented reality solutions will impact every aspect of society, Gourley said. “It’s being commoditized so rapidly,” with three major providers working hard to get the technology into everyone’s home. Part of the discussion must include questions surrounding how adversaries use virtual reality and “how will we protect our virtual realities from their virtual attacks against our virtual realities.”

In addition to questions surrounding morphing realities is the vast amount of generated data that humans cannot begin to effectively process. Some estimates predict there will be more than 1 trillion sensors in the world by 2020, Gourley said.

The Internet of Things (IoT) will not be as secure as current systems, posing “a great danger,” Gourley shared. “Bring it on, and fast, but as we bring these chips into our homes, are we bringing bad guys right into our personal lives, giving them access to our" personal, financial and medical information and private business?”

Much of the first day of the two-day symposium centered on the IoT and the crushing amount of data that will be generated by the proliferation of sensors.

Militarily, the dilemma of harnessing and making sense of information found within the data is a daunting notion, offered Joe Witt, senior director of engineering at Hortonworks. “This gets to the heart of how do you command and control 50 billion assets,” he said.

The generation of sensor technologies will have serious implications—though not necessarily negative implications—on the concept of command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (C4ISR), the symposium’s overarching theme, experts offered.

Faster, lighter, easier, cheaper, smaller—all will have implications for military C4ISR missions that could bring the power of decision making to lower echelons, said Linton Wells, with George Mason’s C4I and Cyber Center, Wells Analytics LLC and National Defense University.

For example, by applying cyber electromagnetic activities, or CEMA, “you change the fight from going against the opponent’s tanks, troops and artillery to now fighting a counter command and control, counter C4ISR … basically at a … battalion level,” Wells offered.

The explosion of commercially available high-fidelity sensors that provide round-the-clock visibility, such as imaging from commercial satellites, track just about every facet of daily lives and can threaten national security and military operations if adversaries are able to track, in real-time, troop movement, for example, Wells said.

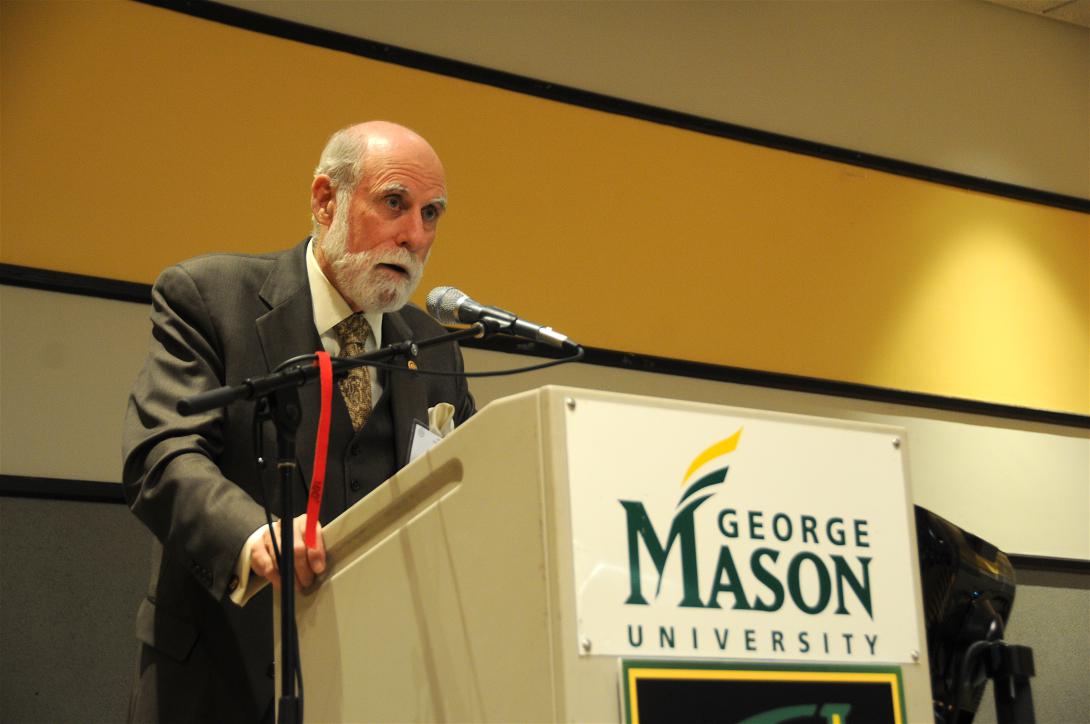

In addition to military applications, symposium attendees were treated to a riveting presentation on innovation by headliner Vint Cerf, touted as one of the “fathers of the Internet” and now vice president and chief Internet evangelist for Google.

One of the most important elements of innovation is creating an atmosphere where employees have “the freedom to fail,” Cerf said. “I can tell you at Google, we are given that freedom. However, there is a price to pay. We have to shoot as high as possible.

“Shoot for the moon, and even if you don’t get the moon shot, you may get something that’s actually more useful.” Cerf recognized the difficulty within the military environment of recommending a freedom to fail notion, but offered that in the research and development arena “you learn a lot more from failures than you do from success” and recommended leaders fold the adaptation idea into the C4I environment.

Additionally, co-location of employees and working in small teams to tackle hard problems have proven valuable when it comes to innovation, Cerf said. “You increase the rate of progress because you don’t spend so much time telling everybody what it is you were doing last week.” That, and the notion that no engineer is more than 50 feet from coffee and junk food, he quipped.

Innovation must be versatile enough to adapt to technology changes, much in the way experts developed some Internet protocols and switch packets to transport data, he said. “Sort of like the postcards don’t know whether they’re going on an airplane or on a ship.”

Additionally, they developed the network so that it is not specific to any one application. “We wanted to make it stupid,” Cerf said. “Just like the postcard doesn’t know what’s written on it, the Internet packets have no idea what they’re carrying. The interpretation of the bits in the packets is done by the software at the edges of the network.”

The fact that the Internet does not know what it’s carrying means networks don’t have to be overhauled for every new application. “I can’t think of a better recipe for innovation,” Cerf shared.

Standards can facilitate innovation, not stymie it, he opined. “[Standards] often confer interoperability on a large collection of things that otherwise would never interwork.”

Finally, Cerf shared he is a fan of virtual machines, which could very well serve as the solution to connect today’s technology offerings with whatever the future has in store. Virtual machines could avoid an “digital dark age,” he said. “What if it can’t read any of our emails, our tweets, our blogs—any of the files that we’ve created. How about all of the pictures we’ve taken?”

Comments