RoboRoaches to the Rescue

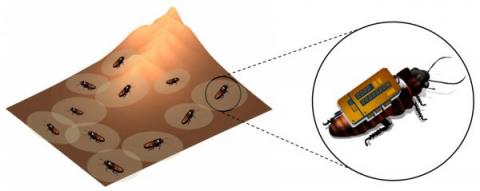

Swarms of cyborg cockroaches may one day aid in search and rescue, military reconnaissance and an array of other missions.

Madagascar hissing cockroaches are about to get a little bit creepier—but it's for a good cause. Research funded by the National Science Foundation could lead to swarms of the insects being used for a variety of missions, including search and rescue in collapsed buildings, military reconnaissance or hazardous chemical detection.

Scientists at North Carolina State University, Raleigh, have developed software that allows the bugs to map unknown environments based on the swarming instincts of cyborg insects, or biobots. The idea is to map areas without access to GPS navigational signals. “They are live insects, but what has been done to them is that there are small backpacks that ride right on top of them, and they have electrodes attached to their antennae and their abdomens,” explains Dr. Edgar Lobaton, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering.

“Signals are sent to the electrodes, and that is what makes them stop or move forward or turn to the right or left,” he explains.

The backpacks are tiny circuit boards with transmitter receivers, which allow the biobots to communicate. “These are weak transceivers, so they can actually communicate with each other whenever they get within a particular range. This is not a long-range transmitter, so they cannot be sending this information to a base station. We don’t want to do that because then batteries are going to be a big issue,” he adds. “They’re going to be able to gather information about who they met within that particular vicinity, and they’re going to share information, such as maybe measurements, to be aggregated,” Lobaton reports.

The roaches also could be equipped with sensors for a variety of missions, including intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance. “Certainly there are a lot of military applications. There could be, for instance, applications where you might be interested in localizing some kind of source in an environment to see if there is a contaminant, pollution or even a source of radiation,” Lobaton says. “On each of their backpacks, they could have different types of sensors—radiation sensors, temperature sensors, sound or chemical concentration sensors,” he offers.

Lobaton cites the Fukushima nuclear reactor disaster as an example of how the cyborgs may be able to help in the future. “You could have these agents exploring over a large area and then trying to determine a particular source of radiation due to a crack in a reactor or something like that,” he suggests.

Although the cyborgs can be controlled to some degree, the intent is to take advantage of their natural navigational skills and swarming instincts. “They’ve gone though evolution due to nature, and they’re very good at exploring. They have their own programming due to nature—they know how to hide, how to explore, how to move along walls,” Lobaton explains. “They have their own built in behavior for doing exploration, so we don’t want to be sending signals to them constantly and telling them to go to the right or to the left, to stop, because at that point, they just become a small robot like anything else you have in the lab.”

In fact, two specific behaviors are most relevant to a roach patrol search and rescue mission, researchers relate. The bugs often will wander randomly in open areas, but sometimes they follow along a wall, especially if they want to remain hidden. “Those are two ways of exploring the environment, and they’re very distinct. Each one of them gives us different types of information about the actual space where they are,” Lobaton states.

The research team has completed software simulations and will present a paper on their findings at the International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, November 3-8, in Tokyo. “Now, we’re doing implementation on a robotic platform. After that, we’re going to test it on the insects themselves. We may not be able to do it to 100 of them, but a few to prove the concept,” Lobaton indicates, adding that the team hopes to have preliminary results within the next year. “After that, it may take a couple of more years to see that as an actual product.” The research also is applicable to robotic platforms, he notes.

Researchers are not exactly creating a Frankenstein version of the cockroach. No bugs will be harmed during experimentation. Earlier versions required a small incision with electrodes going directly into a roach’s muscle groups to stimulate a particular muscle. There’s still a bit of “insect surgery,” Lobaton reports, because the antennae have to be clipped before the electrodes can be emplaced. The circuit board backpacks, on the other hand, are simply glued on and can be removed. “The newer versions are not too invasive,” he says.

Comments