Universities Develop New-School Biometrics

|

|

| The Center for Advanced Studies in Identity Science (CASIS) is helping to usher in a new school of biometrics known as identity science, which goes beyond traditional biometrics of iris scans, fingerprints, palm prints and facial recognition. |

The Center for Advanced Studies in Identity Science (CASIS) is helping to usher in a new school of biometrics known as identity science, which goes beyond traditional biometrics of iris scans, fingerprints, palm prints and facial recognition.

Even as biometrics technology becomes more integral to everyday life, researchers working indirectly for the Office of the Director of National Intelligence warn that some tough challenges have yet to be overcome. Refining facial recognition in crowds, coping with obscurants, finding answers with less than perfect data and addressing flat funding hinder progress.

The current state of biometrics exploration is complex. The technology is being widely deployed for military, national security and commercial purposes and, according to some experts, promises a potentially dazzling future. At the same time, the research is morphing from strict biometrics technology to the much broader area of identity science.“Imagine a world where you wake up in the morning, and your coffee maker recognizes you and makes your coffee just the way you like it. Then, you’re going to head off to work, and as you walk up to your car, it recognizes who you are and not only opens the door but also adjusts the seat and the mirrors and even [matches] the radio station to you,” suggests Gerry Dozier, chair of the Computer Science Department at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University (NC A&T), Greensboro, North Carolina. “You drive into work, and as you walk into the building, the door opens because the building recognizes you, and as you go into your office and sit down, your computer recognizes you and allows you access. When we look at the future of biometrics, all of these things are going to be possible.”

Dozier also is the director of the Center for Advanced Studies in Identity Science (CASIS). CASIS is a consortium of three universities—NC A&T, Clemson and the University of North Carolina Wilmington. CASIS is an Office of the Director of National Intelligence Science and Technology Center of Academic Excellence. It was funded in 2008 with a nearly $9 million grant from the Army Research Laboratory. Its mission is to conduct cutting-edge science and technology research while educating students and expanding the pool of talent in areas important to the United States and its security.

While the future of biometrics and identity science may be bright, the current state of affairs is equally eye-opening. In the commercial world, some laptops are sold with fingerprint pads. Disney theme parks use biometrics to match ticket owners with their tickets. Biometrics data is included in passports and drivers’ licenses. India is attempting to gather biometric data on all of its citizens—more than 1 billion—who do not have government identification. In addition, social media sites use facial recognition to help users automatically identify friends, family and acquaintances in photographs. And, smartphone apps detect the ratio of women to men in a nightclub because, as Karl Ricanek explains, “If you’re a single guy, you want to go to a bar that has more women.” Ricanek is an associate professor of computer science, University of North Carolina Wilmington.

Meanwhile, in the defense and national security arena, the U.S. military has spent many millions of dollars and several years deploying an array of biometrics technologies to Iraq and Afghanistan. The U.S. Defense Department’s Biometrics Identity Management Agency estimates that its Automated Biometric Identification System database contains more than 4 million unique identities and more than 7 million total records. Those records of fingerprints, palm prints, iris scans and photographs for facial recognition are shared with the departments of Justice and Homeland Security. They are used to identify insurgents in Iraq and Afghanistan as well as for border security and criminal investigations.

In addition, traditional biometrics research is morphing into the broader area of identity science, and that change has been reflected in the work conducted within CASIS. “For about the first three years, we were doing work primarily in biometrics. Lately, we’ve been moving more into other forms of identity sciences, such as cyber identification,” Dozier reveals.

Damon Woodard, associate professor, Human-Centered Computing Division, Clemson University, explains that identity science encapsulates traditional biometrics as well as other research areas, such as cultural traits, behavioral interaction, digital artifacts, emotional cues, and the policy and ethical issues surrounding the use of identity. Cultural traits include characteristics such as gender, ethnicity and demographic information. Behavioral interactions encompass how individuals interact with others, primarily online. Digital artifacts include a wide range of data, such as emails, texts and tweets, while emotional cues involve response to particular stimuli.

Microgestures offer insights into a person’s emotional state and can be used for national security, Dozier explains. They indicate whether the lips are compressed or spread out in a smile or the wrinkles around the eyes are engaged in a genuine smile. Such facial nuances indicate if a person is tense or potentially deceptive. “We’re not saying that we’re trying to do lie detection. The goal is to tell if a person is apprehensive, but it doesn’t tell you what the person is apprehensive about,” Dozier observes. The process is similar to that Transportation Security Administration agents currently use, in which they query travelers and monitor responses for signs of tension or deception. “It’s sort of like that, but it’s done in an automated fashion using computer vision and automated learning,” he adds.

“One of the things we’ve been doing using these evolved feature extractors and the resulting templates is to build biometric-based access control protocols. We can evolve any number of these feature extractors, and they perform extremely well. Since we’re able to come up with a number of unique feature extractors, we can use them in place of passwords,” Dozier says. “What we want to do is to get rid of usernames and passwords altogether.”

But just because biometrics technology is widespread does not mean the research is complete. Ricanek confesses to standing on a soapbox regarding the funding issue. “When we get to a certain level of maturity, the funding dollars tend to dry up, and that technology becomes stagnant because corporate or commercial entities just don’t have the deep pockets or the wherewithal to spur technology development like the government,” he emphasizes. “We are starting to see some glimmers of reductions in the research for biometrics and identity management, and that restricts the innovative process.”

He adds that even as advances are made, more needs to be done. “I think there are many applications where biometrics will solve a particular problem, but there are many more applications in which we have not necessarily advanced the technology far enough.” Ricanek cites speech recognition as one example. “Speech recognition has been around since the ’60s. There was a lot of push in the ’70s and ’80s around speech, and in the late ’80s people felt the problem was solved, and we didn’t need to work on it anymore,” he says. “Today, we have Siri, which does a fairly good job of being able to discern speech and make certain queries on the Internet. Siri is OK, but it’s certainly not perfect.”

>Woodard agrees that challenges remain. “You have more applications out there relying on biometrics for identity management, and because of this, there has been a bit of a rush in deploying technology. What we’re finding is that some of the performance we expected hasn’t really been achieved yet. There’s still a lot of progress to be made in biometrics,” Woodard says.

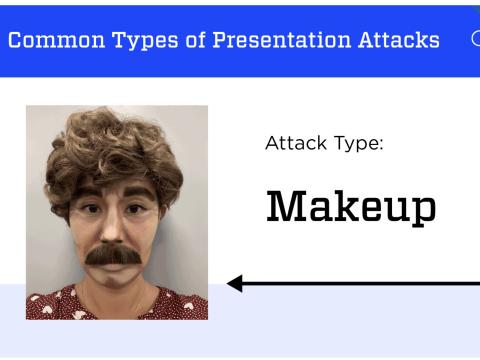

Unconstrained biometrics is another area of identity science that needs more investigation, he adds. “Unconstrained biometrics—biometrics under more challenging conditions—is a fairly active area of research right now,” Woodard says. Some areas the Clemson team is studying include identification in the presence of aging, differentiating twins, recognition using low-quality data, detection of someone using a disguise and recognition of individuals in large crowds. If you look at the research for biometrics—especially for facial recognition—most of the research results reported were using images on the order of a few thousand. If you look at biometrics systems that were actually deployed, where the number of identities that need to be established are in the hundreds of thousands or millions, then you see poorer performance.”

Woodard mentions that when a system contains large amounts of data, processing time also becomes a challenge. “If I collect a biometric sample and I have to search an entire database to find the identity, that can get really time-consuming,” he says.

Keeping all of the identity data secure is another challenge. “With everyone jumping on the biometric bandwagon, there needs to be more research on biometric systems security. This is really important data,” Woodard emphasizes. “Once biometric data has been compromised, you can’t reset your fingerprints, or reset your face, or reset your iris like you would reset a password.”

Privacy offers yet another challenge. “Biometrics assumes one-to-one mapping from a person’s identity to a person’s biometrics. If there’s one-to-one mapping, there are plenty of possibilities for privacy abuse. Let’s say every time you go to the bank, you have to use biometrics. If you go to the insurance company, you use your biometrics. And when you go to the grocery store, you use your biometrics. Because there’s that one-to-one mapping, I’ve just tracked you, and I know everywhere you’ve gone,” Woodard offers.

The final challenge the researchers identify is the lack of professional expertise. As in other science, technology, engineering and mathematics professions, not enough U.S. citizens are studying biometrics to meet the nation’s security demands. “We would love to have more students,” Ricanek concludes.

Comments