Fighting Cyber With Cyber

The Warfighter Information Network–Tactical program delivered a digital transformation, enabling maneuver elements to move faster and provide commanders with vital battlefield information in near real-time. Its flexibility facilitated communications in Iraq’s urban environments and Afghanistan’s mountainous terrain. Although a powerful improvement over Mobile Subscriber Equipment, the technologies are not powerful enough to combat adversaries wielding cyber capabilities.

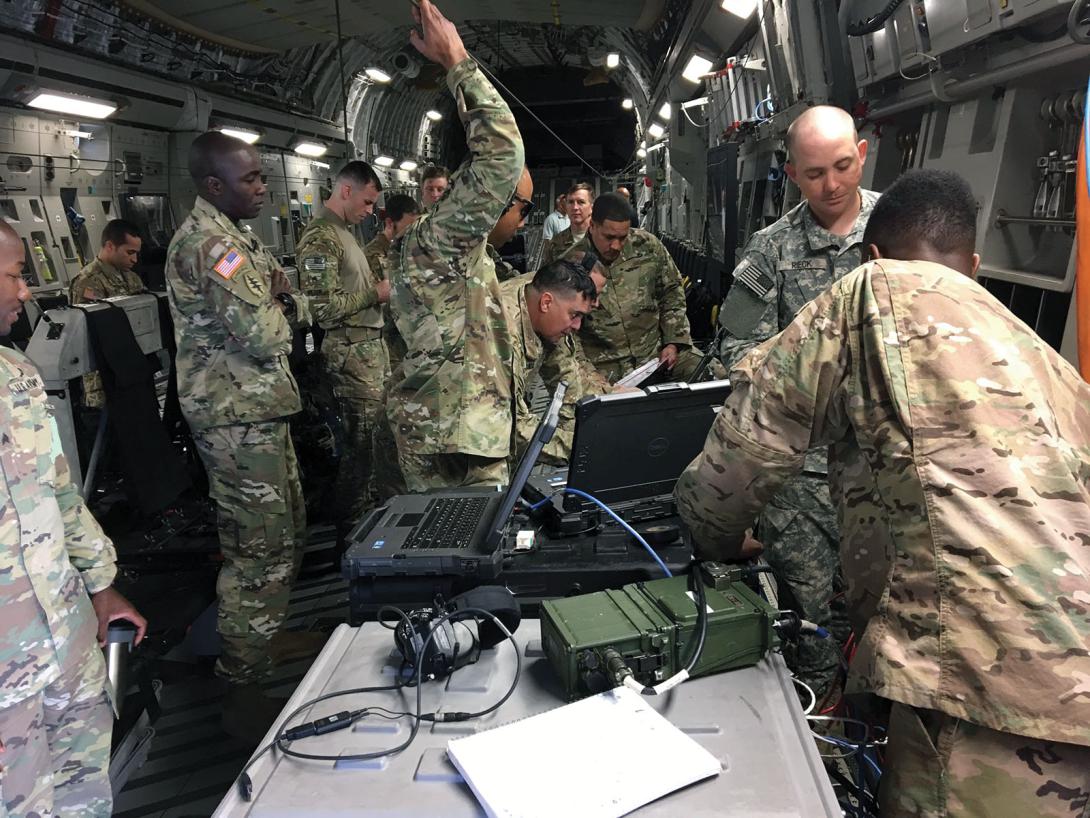

Clearly envisioning a future in which the fighting domain would certainly include cyber, the U.S. Army halted Warfighter Information Network–Tactical (WIN-T) procurements for fiscal year 2018. While retaining the advances of WIN-T increments 1 and 2, the overall program, now called Project Manager Tactical Network, added expeditionary line-of-sight and beyond line-of-sight capabilities. In addition, it now encompasses a scalable suite of integrated tactical network communication, network and cyber management capabilities.

This transition is overdue yet just in time. Through the lens of the modern battlefield, the gaping flaws of WIN-T became evident. As designed, WIN-T offered little protection against electronic interference and jamming. The specialized training Signal soldiers required was a perishable skill set, forgotten when not often used.

In addition, WIN-T’s foundation is built on a hardware-centric architecture. Specific functions require specific hardware and software solutions from different vendors and demand unique and costly skill sets to configure and manage. The added network and security requirements make it difficult for administrators to maintain consistent baseline configurations and increase the likelihood of security breaches.

The dangers of these drawbacks became clear during the past 10 years as U.S. adversaries, particularly Russia and China, grew their cyber capabilities. For example, Russia spent more than a decade in the Baltic region honing and refining its cyber warfighting edge in Estonia, Lithuania, Kyrgyzstan and Crimea.

Ukraine has been Russia’s testing ground for true cyber warfare. According to research by Crowdstrike, Russia planted malware inside a legitimate Android application used by more than 9,000 Ukrainian artillery personnel. This malware “could have facilitated anticipatory awareness of Ukrainian artillery force troop movement.” Because Russian forces could identify Ukrainian troops’ general location and engage them, Ukraine lost 15 percent to 20 percent of its prewar D-30 howitzer inventory during combat operations against Russian-based actors. This cyber attack resulted in real-world consequences.

While Gen. Joseph Dunford, USMC, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, believes Russia is the most military-capable threat to the United States, he named China as the greatest future threat to U.S. security. According to TRADOC Pamphlet 525-3-6, “the Chinese strategy, known as integrated network electronic warfare (EW), combines EW, computer network operations and nonlethal strikes to disrupt battlefield information systems that support an adversary’s warfighting and power-projection capabilities.”

At the national policy level, Chinese President Xi Jinping further consolidated power as he took personal control of cyber policies by creating the Central Cyberspace Affairs Leading Group. Following the United States’ lead, President Xi established the Strategic Support Force as a counterpart to the U.S. Cyber Command and the National Security Agency, choosing equivalent elements from the two agencies and from U.S. federal agencies, including space, cyber and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR).

Building on WIN-T’s communications advances, the Army could address this adversarial march into the cyber realm by adopting a configuration that might be called WIN-T 3.0. The approach would embrace software-defined networking (SDN) to extend virtualization from the data center to network functions. With SDN, the customer can deploy any combination of virtual network functions (VNF), such as routers, firewalls, intrusion detection systems and a proxy server, on general-purpose hardware.

A software-defined network allows for global visibility and centralized deployment and management. Solutions can be deployed quickly throughout the Department of Defense Information Network (DODIN) through software running military-approved standard configurations.

This method would minimize the time, labor and costs associated with buying, installing, configuring and maintaining a baseline on geographically dispersed dedicated, proprietary network appliances. Standard tools, views and architectures down to the user edge in an integrated end-to-end network environment would result in a single, unified network.

The architecture could reduce Signal soldier training requirements as well as the amount of equipment that comprises a command post node. To support a battalion tactical operations center, an enhanced command post node would feature a high bandwidth, high throughput portable satellite terminal. It also would include a secure Internet protocol router (SIPR) and nonsecure Internet protocol router (NIPR) software-defined wide area network (SD-WAN) access cases for connectivity to the DODIN. In addition, SIPR and NIPR virtual network functions access cases would extend DODIN connectivity to the local area network. A satellite communication systems operator-maintainer and an information technology specialist could provide support.

Soldiers would establish WAN connectivity on the SD-WAN router and turn up the VNF stacks. Personnel would authorize the network, complete connectivity and build out the stacks remotely based on mission assurance requirements, bandwidth and support availability, as well as other factors and policies. Because the VNF stacks are built on commercial hardware that supports multiple functions, they can function as a tactical processing node for command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance information and Internet of Battlefield Things sensors, provide local network services or be turned off to minimize the unit’s cyber attack surface.

The WIN-T 3.0 architecture also would support the Army’s Common Operating Environment (COE) foundation. The SDN architecture is a COE-compliant framework that allows the Army to quickly adopt new applications as they are created and approved, become more agile and lethal where it matters, and strengthen the Army’s cyber posture.

In addition, the initiative would support the U.S. Defense Department’s push for centralized applications and cloud-based services. It helps accelerate the department’s move to the cloud and, more importantly, makes data access transparent to the end user whether it is coming from a public, private or community cloud or locally from a tactical processing node. Virtual network functions accelerate network provisioning, provide innovation, increase the network security posture and deliver consistent network access.

WIN-T 3.0 also would assist the Defense Information Systems Agency. The agency’s primary role as an infrastructure provider means delivering the underlying network to facilitate the warfighter mission, including the cloud and cloud services to the Defense Department. In this instance, WIN-T 3.0 would extend the strategic network and services to the tactical edge, which would provide a single integrated communications network. It also would ensure the continued performance of the department’s mission-essential functions in complex threat environments where access to the WAN can be constrained.

Advances in cyber warfare technologies will enable adversaries to attack the DODIN and degrade or deny freedom of movement in cyberspace. During these instances, DISA or the combatant command could choose to fortify Internet access by spinning up virtual network functions during an ongoing operation while security analysts determine how to thwart the cyber attack. Once the operation is complete or cyber attack is neutralized, the commander could draw down its virtual network functions.

Because these functions are built on general-purpose hardware, fully centralized situational awareness is possible and network functions can be authorized and configured to counter cyber attacks in minutes. A single network enables security sensors to collect data into a data lake that can then be correlated to detect the beginning of another potential attack. The Army halted its WIN-T buy to determine if it met the service’s operational needs against near-peer threats. WIN-T Increment 2 doesn’t; however, WIN-T 3.0 could by creating an enabling architecture that fully nests within the Army’s COE framework and addresses many of the network security concerns of the tactical network.

From a networking perspective, SDN checks off every set of standards for the COE while delivering the mission assurance commanders need to execute their warfighting functions. SDN also can accelerate the Defense Department’s cloud migration by extending the DODIN standards into the tactical network, leading to a single integrated communications network that provides full situational awareness.

Lt. Col. Jon Erickson, USAR, is an information technology specialist Signal Corps officer currently serving as the assistant chief of staff, G-6, 79th Theater Sustainment Command.

Comments