HoneyBot Fights Cyber Crime

In the coming months, researchers from Georgia Tech will reveal the results of testing on a robot called the HoneyBot, designed to help detect, monitor, misdirect or even identify illegal network intruders. The device is built to attract cyber criminals targeting factories or other critical infrastructure facilities, and the underlying technology can be adapted to other types of systems, including the electric grid.

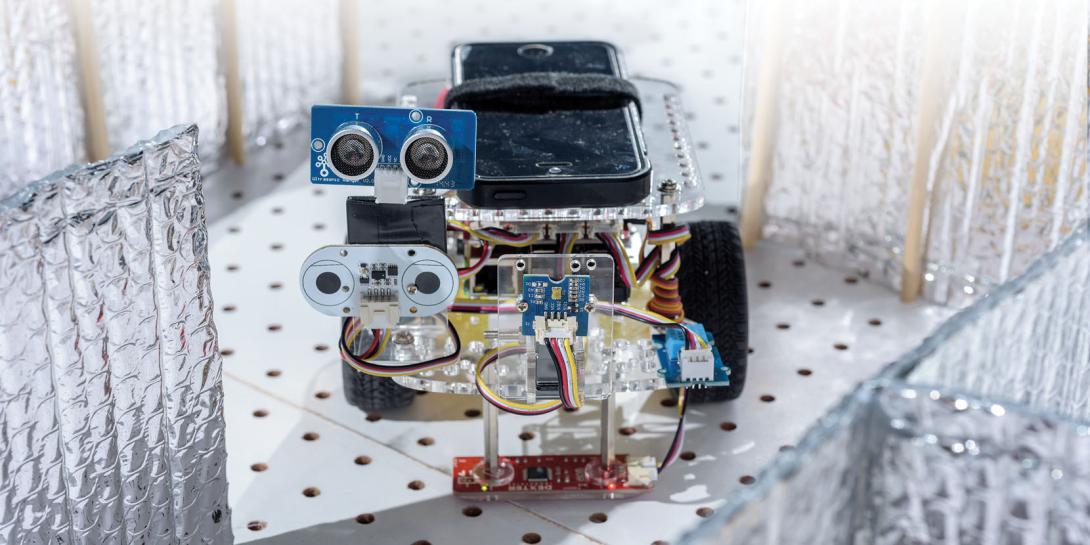

The HoneyBot represents a convergence of robotics with the cyber realm. The diminutive robot on four wheels essentially acts as a honeypot, or a decoy to lure criminal hackers and keep them busy long enough for cybersecurity experts to learn more about them, which ultimately could unmask the hackers.

“The general idea is to get information about the attackers, specifically their tactics and techniques, and even what they know about the system,” says Raheem Beyah, Motorola Foundation professor at Georgia Tech’s School of Electrical and Computer Engineering. “You can use that information for defense and for attribution.”

It is an illegal hacker’s modus operandi that often leads to the culprit’s identification. “You get a pattern of these things. Group A does this a certain way, and they can have a pattern you can track, and then you can attribute this specific attack to group A, or to country A, or whatever it may be,” Beyah adds.

Honeypots are information system resources that serve many different purposes for different organizations, but their value lies in their illicit or unauthorized use, according to the SANS Technology Institute. Beyah describes three types of honeypots: low interaction, high interaction and hybrid systems. Low-interaction honeypots emulate vulnerable systems or services and are technologically simple and easy to deploy. But for more knowledgeable hackers, they also are easier to detect.

High-interaction honeypots are more realistic and less likely to scare off more sophisticated hackers, but they also have a downside. “A high-interaction honeypot allows you to either run the actual software or even control the real system itself. There’s a concern that these actual systems serving as honeypots can be compromised,” says Beyah, who also serves as associate chair for strategic initiatives and innovation in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Georgia Tech.

The HoneyBot is a hybrid system, meaning it is an actual robotic system similar to those that could be deployed on factory floors or within other critical infrastructure facilities. As a real system that an attacker can infiltrate and control, it is a high-interaction honeypot. “Our goal was to build a system that is very realistic. It doesn’t get more realistic than real,” Beyah says with a laugh.

But hackers are only allowed to control it for activities deemed safe, such as meandering around unrestricted areas in a factory. If they attempt to perform unsafe actions—entering forbidden sections of a building, for example—the system switches into emulation mode, duping the hackers into believing that they are still controlling the real thing.

When hackers actually control the system, they can verify its actions by monitoring the data provided by the speedometer, accelerometer or vibration sensors, for example. If the robot collides with an object and comes to a stop, then the hacker will see the velocity go to zero.

When triggered to switch into low-interaction mode, however, the system provides spoofed data to convince invaders that nothing has changed. “If the attacker has access to these sensors, which we assume they do for a cyber-physical system like a robot, then it gets to be really difficult to stop them from knowing that they’re in a honeypot,” Beyah offers. “When we switch to the low-interaction component … that correlation is a challenge and one of the hardest parts of the work.”

The HoneyBot uses a technology framework known as HoneyPhy, previously developed by Beyah’s team of researchers and appropriate for any kind of cyber-physical system. An earlier research project focused on the use of HoneyPhy to emulate a power grid.

Cyber-physical systems are notoriously tough for honeypots to simulate, in part because of the difficulty of mimicking physical movements, processes and machine components such as actuators. HoneyPhy is a physics-aware honeypot framework that addresses those challenges and aims to be easily extensible to all cyber-physical systems.

“If I tell a robot to pick up a box and rotate it left by 30 degrees, physics only allows that object to move so fast based on the motor and the physics associated with the device. It can only do so as fast as physics allows, so we have to model all of that,” Beyah notes, adding that the HoneyBot adapts HoneyPhy specifically for robotic systems.

The HoneyBot has recently gone through testing, the results of which should be published soon. Beyah describes those results as “promising.” Volunteers who represented hackers during the experiment used a virtual interface to control the robot and could not see what was happening in real life. Some actually controlled the robot, while others were fed simulated sensor data. In surveys after the experiment, participants from both groups indicated at similar rates that they considered the data believable. “It’s wonderful for us to build a system and say that we do sensor correlation and all these wonderful things, but if it doesn’t deceive people, which is our goal, then it doesn’t matter,” Beyah declares.

The project is fundamental research, but the device could quickly and easily be deployed if called upon. “It can be used now. It’s a research project that’s duct-taped together, but if we get to a point where we physically deploy it, we can clean up the code and get it out the door in probably two or three months from the initial request,” he suggests.

The team intends to improve the system’s radar, ultrasonic, accelerometer and vibration sensors. “The main goal now is to work on the sensor correlation piece and to expand the number of sensors and improve the correlation process. That’s a nontrivial process,” Beyah reports. “Probably what we will do as we move forward is keep the sensors we have now, but we will probably seek to improve the precision because right now they’re somewhat course.”

Adding sensors also is a possibility. “In theory, you could give the robot vision. You can give it a camera, if you want. It’s hard to spoof cameras, but it’s doable,” Beyah says.

Using the technology on larger robots is a possibility too. The HoneyBot is about the size of a shoebox.

The HoneyBot is funded in part by the National Science Foundation under a project known as Safe and Secure Open Access Multi-Robot Systems. Beyah says the HoneyBot project was scheduled to end this fall, but he expects it to be extended for a year.

While he has no solid plans yet to provide the technology on the commercial market, that is a possibility. “If there’s interest, then we’ll move forward. We would love to talk to partners to take it to market,” he says. “Certainly, I have some interest in commercialization. It’s very important to move things that are very useful to market.”

Comments