Decoding the Future for National Security

U.S. intelligence agencies are in the business of predicting the future, but no one has systematically evaluated the accuracy of those predictions—until now. The intelligence community’s cutting-edge research and development agency uses a handful of predictive analytics programs to measure and improve the ability to forecast major events, including political upheavals, disease outbreaks, insider threats and cyber attacks.

The Office for Anticipating Surprise at the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) is a place where crystal balls come in the form of software, tournaments and throngs of people. The office sponsors eight programs designed to improve predictive analytics, which uses a variety of data to forecast events. The programs all focus on incidents outside of the United States, and the information is anonymized to protect privacy. The programs are in different stages, some having recently ended as others are preparing to award contracts.

But they all have one more thing in common: They use tournaments to advance the state of the predictive analytic arts. “We decided to run a series of forecasting tournaments in which people from around the world generate forecasts about, now, thousands of real-world events,” says Jason Matheny, IARPA’s new director. “All of our programs on predictive analytics do use this tournament style of funding and evaluating research.”

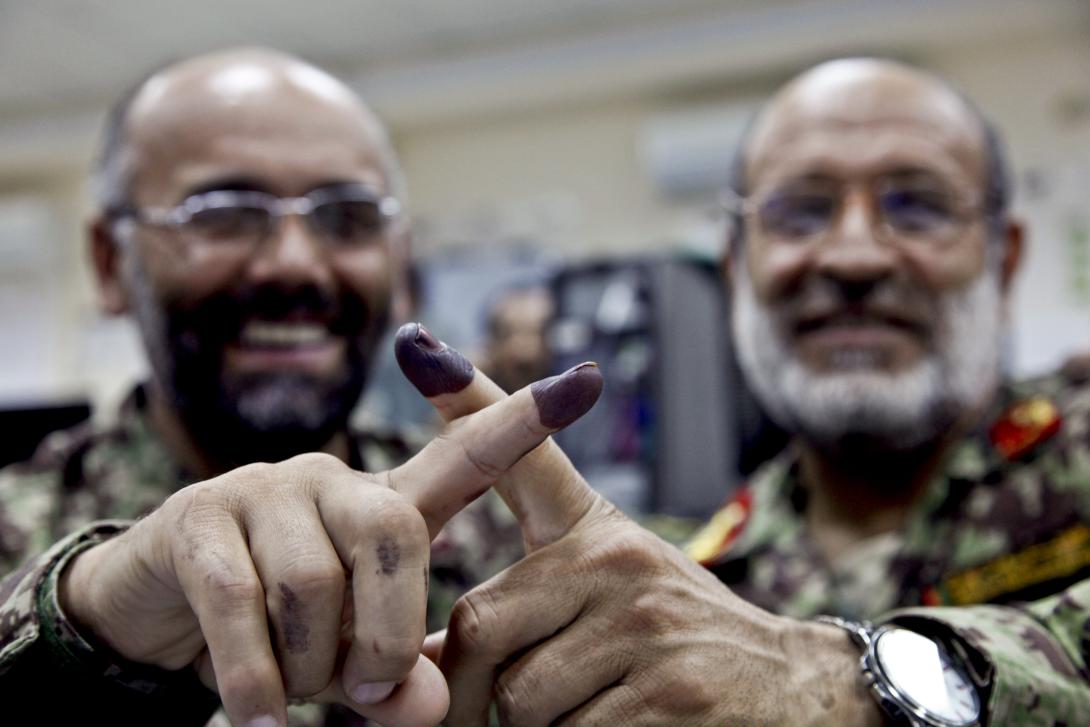

The Open Source Indicators program used a crowdsourcing technique in which people across the globe offered their predictions on such events as political uprisings, disease outbreaks and elections. The data analyzed included social media trends, Web search queries and even cancelled dinner reservations—an indication that people are sick.

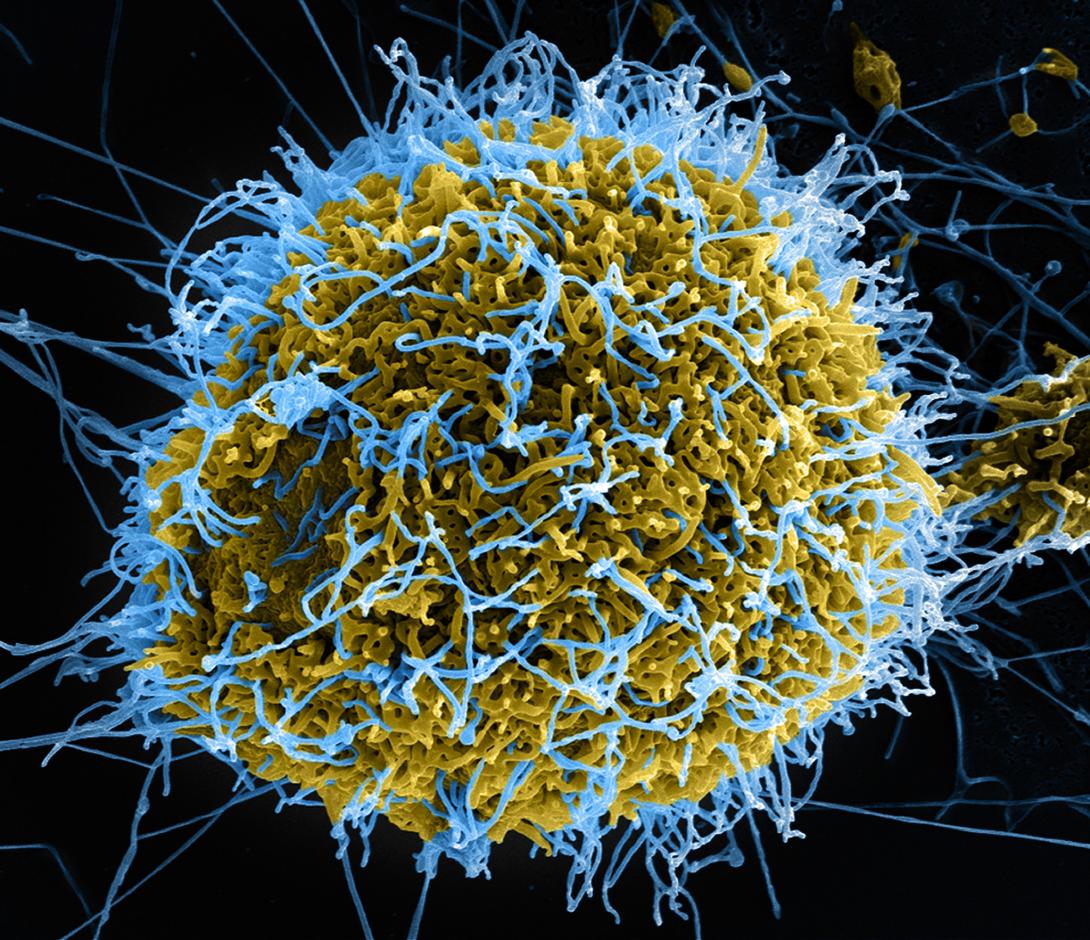

“The methods applied to this were all automated. They used machine learning to comb through billions of pieces of data to look for that signal, that leading indicator, that an event was about to happen,” Matheny explains. “And they made amazing progress. They were able to predict disease outbreaks weeks earlier than traditional reporting.”

The recently completed Aggregative Contingent Estimation (ACE) program also used a crowdsourcing competition in which people predicted events, including whether weapons would be tested, treaties would be signed or armed conflict would break out along certain borders. Volunteers were asked to provide information about their own background and what sources they used. IARPA also tested participants’ cognitive reasoning abilities.

Volunteers provided their forecasts every day, and IARPA personnel kept score. Interestingly, they discovered the “deep domain” experts were not the best at predicting events. Instead, people with a certain style of thinking came out the winners. “They read a lot, not just from one source, but from multiple sources that come from different viewpoints. They have different sources of data, and they revise their judgments when presented with new information. They don’t stick to their guns,” Matheny reveals. The winners also scored very well on critical thinking and logical reasoning exams, he adds.

The program resulted in another important finding. “The very best forecasts came not from an individual, but from a sum across multiple individuals. If you took the sum of forecasts, and you took the average, that would be more likely to be accurate than the forecast of the best expert. That suggests this idea of crowdsourcing or crowd wisdom is something we in the intelligence community should be using more often,” Matheny offers.

ACE, which wrapped up in August, developed software known as Inkling that has been distributed to IARPA’s government partners. The technology draws on research about how best to collect judgments from analysts and how much weight to assign to an individual’s predictions based on that person’s success rate.

The ACE research also contributed to a recently released book, Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, according to the IARPA director. The book was co-authored, along with Dan Gardner, by Philip Tetlock, the Annenberg University professor of psychology and management at the University of Pennsylvania who also served as a principal investigator for the ACE program.

Like ACE, the Crowdsourcing Evidence, Argumentation, Thinking and Evaluation program uses the forecasting tournament format, but it also requires participants to explain and defend their reasoning. The initiative aims to improve analytic thinking by combining structured reasoning techniques with crowdsourcing.

Meanwhile, the Foresight and Understanding from Scientific Exposition (FUSE) program forecasts science and technology breakthroughs. “The purpose of the FUSE program is to look for signals in scientific publications and patents that predict the emergence of a new discovery,” Matheny explains.

For example, before a major breakthrough, scientists often cite a small group of publications with increasing frequency. “That is a growing recognition that there was a result published that was deeply important to a particular scientific problem. You see this spike in citation rates, and then you see this cluster form of scientists who are working off of that initial piece of research,” Matheny elaborates.

Acronym usage also can indicate a pending breakthrough. “When a concept is getting very mature, an acronym will no longer be spelled out. Jargon will not be defined anymore. That is a measure of how familiar a particular community has become with the concepts that form its language,” the director reports.

Along the same lines as FUSE, the recently completed Forecasting Science and Technology program combined the judgments of many experts to develop and test methods of generating accurate forecasts for significant science and technology milestones. The effort included the world’s largest science and technology forecasting tournament, SciCast, which produced public forecasts for hundreds of events.

In the cyber arena, IARPA has received dozens of proposals for the Cyber-attack Automated Unconventional Sensor Environment (CAUSE) program. Proposals were being reviewed in the fall, with contract awards expected by year’s end. Matheny doesn’t predict exactly how many contracts will be awarded because the number will depend on the quality of proposals and, of course, the available budget.

He says the CAUSE effort is similar to Open Source Indicators in that the methods are automated, but the program is unusual within the cyber defense research area. “It’s looking not only at data on a computer or server but also at data that’s outside of a network,” Matheny offers. The program examines whether forecasters can predict when groups of cyber attackers are plotting an event based on a variety of potential indicators, including patterns of Web search queries, black market prices for malware or activity in online discussion forums popular with cyber actors. “We’re really trying to get to the left of boom on cyber attacks, which is of critical importance, given the increasing rate and severity of cyber attacks in the United States,” he asserts.

Also of increasing concern is the danger posed by insiders with special access to facilities and information. The Scientific advances to Continuous Insider Threat Evaluation (SCITE) program examines a broad array of insider threats, including mass shootings, cyber attacks and industrial espionage. “We have a number of insider threat issues we worry about in government as well as in industry. One of those is workplace safety. The Navy Yard tragedy is something we want to ensure doesn’t happen again,” Matheny declares, referring to the 2013 incident in which a lone gunman at the Washington Navy Yard in Washington, D.C., fatally shot 12 people and wounded three others.

Regarding insider espionage, Matheny compares SCITE’s goals to those of lending institutions. “The credit card companies want to detect ... what appears to be anomalous purchasing behavior. But if you’re traveling, there’s an anomaly that the bank detects, and it may then require that you call in to use your credit card,” he explains. “What we would like to do in the intelligence community is to have that kind of fraud detection with as low a nuisance level as possible.”

Technology developed under the program could be used commercially as well, he allows. “In fact, industry is interested in the general problem of insider threat detection—not just because of workplace safety but also because of intellectual property protection,” he adds.

Overall, predictive analytics is important to the intelligence community for a number of reasons, Matheny says. In part, the science will help agencies measure the accuracy of their predictions and the rate of false alarms.

Still, the predictive analytics arena presents challenges to overcome. As an example, he cites the Mercury program, which examines classified signals intelligence data and its potential use in predicting a wide variety of events, such as military mobilizations, terrorist attacks and even disease outbreaks. “Classified data is expensive to collect. It’s expensive to process and to analyze and to store. So you really want to collect it and use it when it’s most valuable,” Matheny states.

Mercury will study the types of events classified data can be most useful in predicting. The program will compare the accuracy of confidential and open-source information, and it will examine what happens when the two are combined. For example, analysts may foresee disease outbreaks even sooner if signals intelligence is added to publicly available information. Mercury also was undergoing the proposal review process in the fall, with contract awards expected soon afterward.

While it is not unusual for scientists to use history to develop forecasting technologies, IARPA requires the prediction of entirely new events. “There are a few reasons for forecasting real events. One is it makes for a great research program because there is no way to cheat. It’s pretty easy to predict history. You know what happened already, and it’s easy to fit your theory or model around history. It’s much harder to predict something that hasn’t happened yet,” Matheny explains.

He recalls a quote attributed to Yogi Berra and a slew of others: Prediction is difficult, especially about the future.

“That’s exactly right,” he says.

Comments