Intelligence Analysis Needs Course Change

Legacy methods and arcane rules are hamstringing U.S. intelligence analysis at a time when it should be innovating. From training, which needs to shift emphasis to more basic skills, to collection and processing, which must branch into nontraditional areas, intelligence must make course corrections to solve inflexibility issues, according to a onetime intelligence official.

Previous shortcomings led to the establishment of analysis standards that have become too rigid for today’s intelligence needs, says Mark Lowenthal, former assistant director of central intelligence for analysis and production. Lowenthal, who teaches an AFCEA PDC onsite course on U.S. intelligence that is also available in a virtual format, states that training must change to compel the type of analysis necessary to meet the new threat picture.

Intelligence analysis changed substantially in the wake of the 9/11 attacks and the onset of the Iraq War, Lowenthal says. Recognizing that analytic deficiencies existed then, Congress and the intelligence community created the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) position. Along with this came congressional requirements for what analysis should look like. These evolved into analytical standards that emphasized analytic training, but the attempt to bring it about on a community-wide basis largely has not succeeded, Lowenthal states. Analytic training is still stovepiped by agency.

These analytical standards are the new battleground in analysis training, he continues. The conflict lies in how the standards are being interpreted, as many analytical managers have taken to using the standards as a checklist rather than as guidelines. The result is to subject analyses to an acid test. “If your analysis doesn’t check off every one of these boxes, it cannot go forward,” Lowenthal reports. “The standards are a guideline—what good analysis should look like, and these are the things you need to think about. But to argue that you have to do each and every one of them, or the analysis can’t go forward, I’m quite convinced is not what the DNI had in mind [when formulating these standards],” he declares.

What makes this problem worse is that the standards are now written in law. “So, if an analyst doesn’t check off all the standards, is he in violation of the law?” Lowenthal questions. The argument that you can perfect analysis is illusory, he claims. “It misunderstands the inherent nature of intelligence analysis.

“You rarely have complete intelligence,” he continues. “You are going to different points of view as to how good the intelligence is … there are subtleties, there are uncertainties, and we rarely have absolute truth.” At the end of the day, it is up to the policymaker to determine how to view the opinions expressed in an analysis, he adds.

Fixing intelligence analysis can come down to basics, Lowenthal offers. One skill sorely lacking among many intelligence trainees is the ability to write effectively. “They literally can’t write well,” he charges. “I’ve joked that this is because they spend all their day texting and they sound like a character out of a 1950s western … but I find that my students really can’t write well, and that’s a major issue. You have to be able to write well, quickly and to the point.

“If you don’t like to write, then [analysis] is a really bad job,” he continues. “You really need to think about another profession.”

He also expresses concern over these students’ ability to discriminate among sources. They tend to spend too much time on social media, which lacks an intermediating authority that judges the worth of each piece of information. This may have led to a decline in students’ critical skills, he suggests.

And social media itself poses different challenges. Pursuing relevant information on social media is, for the most part, a waste of time because of the large amount of chaff. Lowenthal notes that Sir David Omand, the former director of the Government Communications Headquarters in the United Kingdom, has suggested that social media should be treated as a separate -INT known as SOCMINT because it’s a separate open-source stream.

But these increasingly large amounts of data can be overwhelming to the decision maker. In many cases, the customer cannot understand it in its raw form. “Data are like a foreign language,” Lowenthal offers. “Maybe we should be thinking about data as a language set, where we need a bunch of people who can interpret data and then give it to the analyst.”

Effective data depends on the algorithm, he notes, referring to a former colleague who used to state that an algorithm is just an opinion written in code. “Data is not ground truth,” Lowenthal states. “It’s an interpretation of number sets, and different types of data are analyzed and look different. I need a set of people who can interpret the data for me just like I need someone who can translate Chinese for me.” This interpreter would provide the translation to the analyst, saying what he or she believes the data is, its reliability and the problems with the data set—just as is done with other -INTs, he says.

One lesson educators can take from the military is to “train the way we fight,” he says. The intelligence community does not do that, he charges, opting instead to train as individual agencies instead of as a community. “We don’t put enough emphasis on training and education the way the military does. It’s a career-long activity; it’s not just checking a bunch of boxes before we put you at your desk after six weeks.”

Students also should be taught about dealing with uncertainty. How to deal with it and express it are needed skills, he adds. This is especially important with cyber, where information often defies easy attribution.

Experts who focus on the future of analysis often cite artificial intelligence (AI) as essential to managing large amounts of data, but Lowenthal warns against excessive expectations. “We’re not at a point yet where AI is going to achieve what we want it to do,” he states. “It’s very important in terms of pattern recognition and working through sets of data, but again we need a person to interpret it for us.” AI is not likely to change analysis in the near term, he concludes.

But improvements in the intelligence community need not wait for technology to advance. For example, one thing the pandemic has shown is that the United States needs better medical intelligence, Lowenthal says. “We are not well-structured right now for medical intelligence,” he states. Existing assets include the National Center for Medical Intelligence at Fort Detrick, Maryland; and the Centers for Disease Control, which includes people cleared for Top Secret/Sensitive Compartmented Information (TS/SCI), but the United States should start thinking of a national intelligence officer for health, he says. The country also needs offices dedicated to epidemiology and pandemics.

Lowenthal offers that terrorism, crime and narcotics are all similar issues to national health. At one level, they are foreign intelligence issues, but at another, they are domestic issues. The United States has figured out how to parse the first three topics; it can easily do the same with national health, he says. “We are not well structured for it, and we haven’t paid enough attention to it, and that’s going to have to change.”

This will require hiring people with biological and medical expertise, such as epidemiologists and doctors, and then translating their findings and analyses so that government officials can understand the intelligence. “We need to put more emphasis on this because it’s going to keep happening,” he predicts. “This is a major warning shot, and we need to be better structured to do it.”

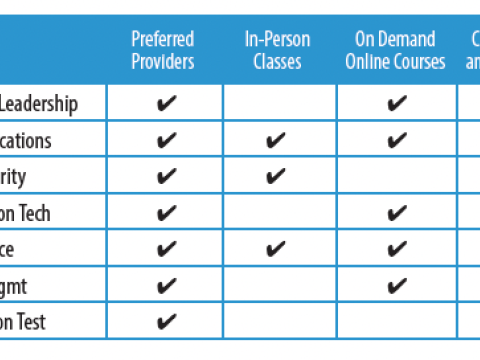

Mark Lowenthal teaches the AFCEA online/virtual course, U.S. Intelligence: An Introduction. Click the links for more information.

Iraq War Intelligence Failures Led to Current Limitations

The incorrect intelligence assessment of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction capabilities was one of the two main causes of the new analysis standards, but that assessment may not have been the primary driver behind the U.S. decision to invade Iraq, says Mark Lowenthal, former assistant director of central intelligence for analysis and production.

“The estimate did not cause the war,” Lowenthal maintains.

“Clearly, there were flaws in the Iraq experience,” he states. “Number one, we were wrong.” Yet, he charges, the decision makers who led the United States into that war did not read that estimate.

Lowenthal emphasizes that the estimate was not written for President George W. Bush or Vice President Richard B. Cheney. The request for the estimate came from the U.S. Senate, for which it was written. The Senate wanted it for the vote to go to war, he says.

Lowenthal relates that he was the officer commanding CIA when the request for the estimate came in one Sunday afternoon in October 2002. While 9/11 provided the emotional spark for intelligence reform, most of the legislation that directed it had the Iraq estimate mistake in mind.

He offers that the biggest flaw that doomed the estimate was that analysts did not think of Iraq as a place. “We thought about Iraq as a bunch of weapons systems. What does their nuclear program look like, what does their missile program look like, what does their CW/BW [chemical warfare/biological warfare] look like? We didn’t think about the overarching picture of Iraq.

“And there was really no ground truth available in Iraq,” he continues. “Everybody in the Iraqi government lied to everybody else, up and down the line. And so, it would have been incredibly difficult to have established ground truth in Iraq.

“Some of our sources turned out to be totally unreliable, which is another issue … but the main issue was we ended up not thinking about the place in which this was happening, what is it like. Had we thought about that … I’m not sure it would have changed anything.”

Comment

The article touches on

The article touches on several key points: primarily analytic competence with the ability to interpret available data well enough to present a picture that gets the point across. Although I wasn't an intelligence analyst (forgive me, please), I was the contractor PM for the Community On Line Intelligence System for End-Users and Managers (COLISEUM) Program at DIA from its inception until 2001. Nearing successful completion of USAINSCOM's Intelligence Production Management Activity's Automated Requirements Management System (ARMS) initiative to automate the Army's management of intelligence production, I was approached by DIA-DO in 1992 to essentially rescue their Intelligence Production Management (DODIIMS) project. Considering the state of how intelligence production was managed at the DIAC, this was a contract opportunity I almost turned down. The difficulty with attempting to automate the production management process was that every intelligence production entity had their own way of doing business (stovepipes), not to mention "rice bowls" they weren't willing to share (a major stumbling block that continues on a larger scale today with inter-agency “silos”). I recall seeing a poster in the DIAC when visiting for the first time: "The wonderful thing about standards is that there are so many to choose from." To make a long story short, I agreed to put a small team together to conduct an analysis of DIA’s intelligence production management process, which included key stakeholders from the then existing intelligence production entities, which I won't go into here. I saw this as the necessary first step needed to prevent being blamed for a resulting system broken out of the box. Fortunately, the government PM saw the wisdom in obtaining stakeholder buy-in, which led to the publication of the DOD Intelligence Production Program (since revised) and the development and deployment of COLISEUM using a rapid prototyping approach (DevSecOps in today’s parlance). The success of this project was recognized with award of the Computerworld-Smithsonian Medal for "heroic achievement in IT" (as well as DIA contractor of the year); but I digress.

Not to date myself, but my career in IT began with punch-card machines in 1970, and thereafter with varying IBM mainframes, DEC minis, and then transportable computers to desktops as hardware platforms evolved. To my knowledge, I was the first person to jump from a perfectly good airplane with a transportable computer (thanks to HP) to subject it to ruggedize testing for JSOC-J2. During that assignment, I was further impressed that the hardware we were procuring were tools to aid our intelligence analysts to accomplish their intelligence assessments quicker than indelible ink and acetate.

Being an IT systems analyst/programmer at the time, I dealt in the digital world where things could be reduced to on or off, but I also understood that intelligence analysts deal in the analog world where multi-source information must be subject to certain processes, e.g., link analysis and risk assessment, to produce a finished product intended satisfy a particular consumer for mission planning and execution.

My interest in self-defense firearms training has demonstrated there are five levels of competency, which I find myself adapting to most any discipline, not the least of which includes intelligence analysis. They are: Intentionally incompetent, Unconsciously incompetent, Consciously incompetent, Consciously competent, and Unconsciously competent. Most of these speak for themselves (especially to the poor writer), but with the tools, training, experience, and attitude required to perform at peak, the intelligence analyst can become unconsciously competent; that is, capable of performing and producing without a discernible thought process.

The ability of the analyst to function flawlessly (unconsciously competent) in high-stress situations is rare in today’s fast-paced, high-tech environment with an ever-increasing demand to produce finished actionable intelligence from uncertain sources; however, this fact is due to flawed processes and inadequate training, more than a lack of motivation. More common is the analyst who performs his/her analysis “by the numbers” (consciously competent), connecting the dots by adherence to a strict set of rules (pseudo-AI), making sure every base is covered prior to moving to the next step in the analytic process. Perhaps without realizing precious time is being spent, the consciously competent analyst is delaying the production of a time-sensitive product that could be critical for an operation whose mission is to save lives.

I am in no way criticizing intel analysts who play a key role in mission planning. It’s the standard, or “what” they are trained to satisfy that effectively determines the quality of the product when it should be the process, or “how”, analysis is to be performed. In the intelligence Production domain, the implementation of the DODIPP (the process) and COLISEUM (the tool) undoubtedly improved the quality and speed of Production by defining responsibilities and lanes for all stakeholders.

At a DODIIS conference just after former Ambassador Negroponte was appointed, I got him to the side and indicated I knew what he was up against, having heard President Bush announce that the ODNI was established with the mandate to bring the IC together. Giving the new DNI my COLISEUM capabilities elevator pitch in the minute I had with him, I explained that with just a few tweaks in National policy and procedure, COLISEUM could be the answer to his marching orders. With that, he replied he would “need time to think about it”. I wondered why he needed more time since it was obvious how COLISEUM transformed the DOD intelligence production process – to include quick response RFIs – until I realized the one-size-fits-all approach would mean the other Agencies would be extremely reluctant to contribute even a miniscule part of their budgets to adopt COLISEUM even though it would be chump-change. Add to this the software behind COLISEUM at the time just migrated from thick-client to thin-client server-side technology. To boot, a multi-level security domain solution was imminent (testing preparation underway at NSA) with TS-SCI already running over JWICS, and SIPRNet and NIPRnet pending accreditation, which would mean Agencies would have to defend their huge IT budgets. “Not invented here” came to mind then and now.

The declaration, “Garbage in – Garbage out” remains, whether it is a computer’s processor or an analyst’s brain doing the processing; it is just that one is much faster at doing the computations than the other. Mr. Ackerman is correct, both in his assessment that intelligence analysis needs a course change and improvements in the IC need not wait for technology to advance. We need not wait for AI either because how computers “think” (at least in the near term), will not differ from those who write the code. We have been trying to apply AI to analytical processes since 1980 in more than one organization and we haven’t made any real breakthroughs (that I am aware of) yet. At best, predictive analysis has proven to be semi-reliable but not wholly trustworthy.

To respond to the “evolving threats” of today, the ODNI should seriously look to DIA’s past (I would recommend circa CY 2,000) to examine what changes made by that organization back then greatly improved the DOD intelligence production process, and then extend the model to the entire IC – to include DHS. Cybersecurity, Cloud computing, DevSecOps, and other new but synonymous buzzwords are all well and good for technology sake, but IC-wide shared methods, processes, and procedures are just as much needed in today’s threat environment to create a true and workable “all-source” collection, production, and dissemination EIS capability.

Tony Goe

Director, Government Services

CyberLocke, LLC

480-490-1437

a.goe@cyberlocke.com

This article is a valuable

This article is a valuable sharing of insight from someone with "Boots on the Ground" credentials. Until the end.

Mr. Lowenthal calls for a "national intelligence officer for health" . He acknowledges existing assets like the Center for Disease Control (CDC) fail to produce reliable medical intelligence. The dismal failures of the CDC exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic support his claim.

If we cannot reform or eliminate the CDC, creating another bureaucracy will lead to the same outcome. Plus, more of the endless turf wars that have made the Department of Homeland Security an endless, expensive bad joke.

Larry makes an excellent

Larry makes an excellent point. What happened to the National Center for Medical Intelligence (formerly Armed Forces Medical Intelligence Center)? Is it because they are a DoD entity there appears to be no involvement - not even collaboration? Who has the assignment/responsibility for producing the medical intel? Lots of questions & comments but I hope someone is working the issue.

Comments