Improving Procurement Through Practical Measures

The U.S. Army is adjusting its Network Integration Evaluations to facilitate acquisitions more rapidly. Calls from industry and soldiers themselves have precipitated the moves. As companies face reduced funding streams, and technology advances in increasingly shorter intervals, implementing briefer time frames between testing and deployment is imperative to remaining viable on and off the field.

Service leaders continually voice their commitment to keeping the evaluation events running despite budget cuts forcing major adjustments in Army programs. These officials reiterate the necessity of putting technologies into the hands of soldiers early and ensuring that pieces will interoperate to form the overall network down the road. But the evaluations have not resulted in the procurements originally expected by various parties.

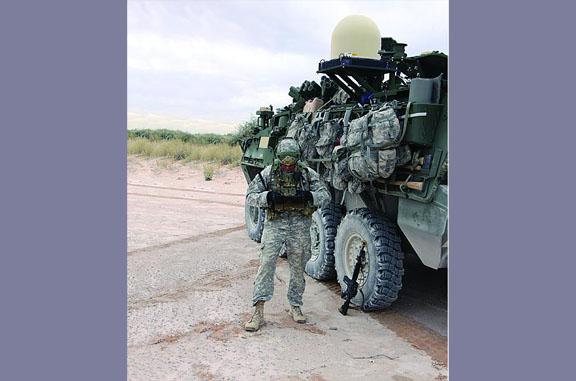

The breakneck pace of running two wars until recently meant pushing out capabilities as fast as possible often took precedence over proper integration. The Network Integration Evaluations (NIEs) were stood up to address that issue. Col. Mark Elliott, USA, director, G-3/5/7 LandWarNet-Mission Command, says the U.S. Army saw the opportunity to bring in industry to help find the solutions for interoperability and to assist the government with taking advantage of innovation. Through the process, the Army has listened to what the private sector has to say and is implementing changes.

Col. Elliott explains that the service branch has put the 18- to 24-month lead time requested by industry into strategy guidance. Now the focus is on the push to identify resourcing gaps earlier. Brig. Gen. Dan Hughes, USA, program executive officer for Command, Control, Communications-Tactical, adds that industry has assisted the Army to inform its acquisition strategy in multiple programs, aiding with how to field, compete and lower the cost of equipment moving forward. The calls for procurement reform are coming “absolutely from both” troops and industry, Gen. Hughes explains. The private sector wants to see a return on investment because participating in the NIE is expensive. Soldiers want the changes because they want fully operational gear as soon as possible. “We have to make our force structure capable of doing the mission it needs to do,” the general says.

Building in the aforementioned lead time should have positive results for both sides. The Army will go to developers with its new challenges, requirements or deficiencies to explain what it needs. If companies do not already have the solutions on hand, they can begin to develop them and run them through one or two events to ensure the capabilities deliver what is expected while the Army puts some funds against it. If all goes well, technologies move more quickly into capability sets. NIE leaders are unsure at this point of what that overall time line will be from start to finish.

“The NIE is an evolving and adaptive process,” Gen. Hughes says. Already the Army is procuring technologies such as routers, switches and installation kits. Over the last decade-plus of war, the approach has been to buy what soldiers need when they need it. The current environment demands a different approach. “We have to look at what the need is,” he states. As the Army transitions to a force preparing for, rather than actively engaged in, war, leaders must focus on resources for the size the service will be in the coming years.

Despite the push for changes, much in the NIE works well. “The number one piece of the NIE, which I think is critical, is soldier feedback,” Gen. Hughes says. During a normal acquisition cycle, soldiers would not touch a technology until seven years into the process. Now, that input comes within months, allowing the Army to adjust acquisition programs. One important area affected by this change is user interface. If soldiers dislike the interaction with a tool, they often stop using a resource. Having troop input ensures viability downrange.

Gen. Hughes says some excellent technology that has come through the NIEs unfortunately included bad interfaces, resulting in soldiers disregarding it. In the tactical environment, certain capabilities have had such complex interfaces that functions such as establishing a network or even turning on a device were too much of a hassle. These problems eliminate the likelihood of use in the field. The NIE can help the acquisition process by ensuring that equipment has its complexity in the box, not in the parts soldiers have to manipulate, he adds.

During the past year, NIE officials have experienced unusual opportunities to test just how to handle acquisitions and other assets of their events. They have contended with sequestration along with a government shutdown, necessitating more scrutiny over how funds are spent. Col. Elliott says the exercises are becoming more efficient as the Army comes out of the wars. “I think anyone would tell you the military is trying to become even more and more careful about how it spends money ... we at NIE are no different,” he says. “We are trying to be very, very smart at how we’re doing that.”

Both the general and colonel emphasize that procurement is not the entire story of the NIE. “It’s more than just acquisition,” Col. Elliott states. “It’s about how we are delivering new capabilities and how we are using them in new environments... I would say that’s probably the biggest misconception that this is only about acquiring. One thing we have to remember as an Army is that not everything needs a material solution.”

To that end, NIE officials remind developers that the Army wants mature capabilities for these events. Leaders are looking for solutions the service branch can acquire readily and that will fit well inside the process. “It’s all about the capabilities we’re pushing out the door,” Col. Elliott says. Solutions that do not align with Army architecture needs are unlikely to make the cut. The various events incrementally make the network better. Gen. Hughes says if the NIE makes capability one iota better, it advances the goal to give soldiers a good network. “Soldiers deserve a network that is always on,” he explains.

In the past, tests were run in programmatic isolation. Various effects on other pieces of the network remained unknown until late in or even after the development process. “On the materiel side, what we’re doing at the NIE [is] an integrated test,” Gen. Hughes explains.

NIE personnel are testing various ways to increase efficiency in the events, most notably through introducing more live, virtual, constructive, or LVC, options. They are carrying out some restructuring at Fort Bliss, Texas, to determine the right mixture of in-person and simulated options. The measures should pay off for the Army long-term as current events demand higher levels of proficiency. And while tactics, techniques and procedures are important, the materiel side specifically has been refined. Gen. Hughes explains that the network has become dramatically better already but reductions not only in money, but also in manpower, are forcing additional improvements. Both officers agree the Army has to become smarter about putting all its solutions together. With faster, better understood procurements, industry and the military will save resources and time. So the push to make changes is not arbitrary nor motivated only by profit.

And Col. Elliott believes they are getting smarter. “I would tell you, the feedback we’re receiving from soldiers in theater—it makes it all worth it,” he states. He expects to see even more improvements, including through acquisitions, in the future. Leaders also are looking at issues doctrinally to understand other implications.

contact: Rita Boland, rboland@afcea.org

Comments