A Million Keys To the Castle

|

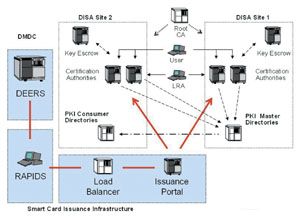

| The U.S. Defense Department’s Public Key Infrastructure (DOD PKI) program is a massive effort to provide personnel with a secure means to access and share information across the Internet. A key feature of the program is the issuance of common access cards (CACs) to personnel. These smart identification cards can have software credentials added to them, allowing users to access secure e-mail and data on military computer networks. |

The U.S. Defense Department has successfully deployed a major program to provide secure access to its communications and computer networks. Over the past five years, the initiative has put an architecture into place that tracks, certifies and approves a variety of transactions—from verifying personal identification to encrypting messages—for millions of users. Government officials claim it is the largest and most successful effort of its kind in the world.

Information assurance across the relatively ungoverned Internet has worried security experts for many years. While the Internet allows instant access to data and applications, its anonymity opens avenues for fraud and abuse. The life-and-death nature of military operations requires a higher degree of security than is commonly found in the commercial world. Everything from requisitioning supplies to mission planning now occurs electronically across military systems. By providing a verifiable means of tracking and approving a variety of requests, the services enhance both their efficiency and security.

Launched in the late 1990s to improve identity management across the Internet, the Defense Department Public Key Infrastructure (DOD PKI) program is overseen by the National Security Agency and the Defense Information Systems Agency. According to Gilbert C. Nolte, director of the DOD PKI Program Management Office,

The Defense Department provides its personnel with three types of credentials through the program. Every employee issued a CAC also receives an identity credential or certificate. Personnel with e-mail accounts receive an e-mail encryption and digital signature certificate. However, not all individuals require three certificates, causing some variation in issuance numbers, Nolte explains. Certificates also are issued for access to equipment such as Web servers to enable secure socket layer access to the secret Internet protocol router network (SIPRNET).

Nolte maintains that the major advantage of PKI is that it can replace user names and passwords completely by providing an authenticated identity credential that can be used to access data or applications. This trusted key can be part of stronger access control mechanisms that permit more granular information control. “That’s where you really start to unlock the power of a digital identity. If I have a way to identify myself electronically in a verifiable and trusted way in cyberspace, then I can use that identity to access a variety of data or applications and not give access to others,” he says.

This authentication capability can add personnel to secure access lists quickly, enabling them to share data. However, Nolte adds that PKI allows strict control over who is permitted to share and process information.

During its initial implementation in the late 1990s, the DOD PKI program issued certificates specifically to users and servers managing secure e-mail. The system uses local registration agents (LRAs) to validate users’ credentials. As the program grew to encompass the entire Defense Department, the challenge was to provide the system with enough registration agents to allow it to scale up to meet user demands, explains Bill Schell, president of August Schell, the Rockville, Maryland-based firm that helped design and implement the DOD PKI system. He adds that the commercial software for the LRAs and for many of the architecture’s registration components was never envisioned to support millions of users.

Another initial requirement was the ability to deploy the PKI system to geographically dispersed locations. Part of this goal was to issue two types of certificate authorities (CAs): an identification CA for releasing certificates and another for authorizing e-mail credentials and certificates. The e-mail certificates consist of a digital signature for authenticating e-mail and a key encryption certificate that allows other vetted users to send encrypted e-mail to the recipient. The DOD PKI architecture currently supports 19 active CAs, notes Michael Brown, August Schell’s director of security and information assurance.

Certificates and CACs have a three-year life span. Program policy stipulates that when user keys expire, they are not renewed but are completely updated. For example, when a user requires a new certificate, the old certificate is revoked and a new key pair and certificate are issued. Brown explains that the revocation interface to the CA is issued separately.

Despite the success of deploying the architecture across the Defense Department, Brown cautions that PKI is not an easy technology to master and due diligence is vital. “There are still not a whole lot of people who understand how to use certificates, and it does require experienced people to administrate it. But a second requirement is testing. It’s obvious, but before something is implemented in PKI, it needs to be tested so that it doesn’t impact operations or that there are no unintended consequences,” he says.

|

| Operating from two primary sites, the DOD PKI architecture has allowed the military to issue nearly six million smart cards to active duty and civilian personnel. The system features the use of certification authorities to determine user access to different types of data. |

Another feature can recover lost user keys. The old retrieval method was complex, time-consuming and prone to error because it required two other users to send half of the key, in encrypted format, to the user who then decrypted and combined both halves into a key. The new process allows users to recover a lost software key by themselves provided they have a valid CAC. The card permits the user to access the system’s database to retrieve the old key.

While the DOD PKI program has adapted to support the entire department, recent military operations have posed challenges. During the buildup for operation Iraqi Freedom, for example, the system had to issue large numbers of CACs and certificates to reserve personnel called to active duty. To satisfy this surge, the program issued PKI-ready cards. These documents provide basic military identification that can be augmented with additional PKI certificates when soldiers reached their bases.

Nolte explains that the deployment tested many of the parts of the DOD PKI program’s smart card rollout effort that had been underway for several years. The CAC effort had developed a central issuance capability that permitted the pre-arranged mass deployment of cards to newly activated units and to forces returning from operational theaters whose cards were near expiration.

While the buildup and deployment for operations in

An important tool used to issue CACs across the Defense Department is the real-time automated personnel identity system terminal. Some 1,800 terminals are located at

Usage was another challenge of the

The DOD PKI program team has spent the past two years developing a solution to this bandwidth concern. It is now deploying the robust certificate validation service (RCVS), which features a technology called the online certificate status protocol (OCSP). The OCSP eases PKI loads by moving certificate checking away from individual workstations and up to the enterprise level. Nolte adds that this capability is necessary because CRLs have grown to 40 megabits in size since 2003. “Now all the client needs to do is a certificate check back to our RCVS nodes. That is a quick lookup and response—less than a second,” he says.

To enhance its certificate validation capabilities, the six additional RCVS nodes are being installed on the nonsecure Internet protocol router network and another one will be put on the SIPRNET. Nolte explains that more credentialing capabilities must be established on the SIPRNET because more information sharing is being done in a secret environment between the Defense Department and other federal agencies such as the departments of Homeland Security and State. “We are connecting our networks and sharing information, but there’s a whole lot of information out there. So what should and shouldn’t we share, and how can we use capabilities like PKI not to limit but to ensure sharing?” he offers.

The program is deploying a new capability called smart card logon. This feature allows personnel to use the PKI credential on their CACs to log onto a network, eliminating the need for user names and passwords. But to enable this capability, the system must determine a credential’s validity in real time. Nolte explains that the OCSP architecture will enable this critical system to function.

Validation also will become more important as the Defense Department infrastructure begins to emphasize information sharing between the services. One feature of the military’s transition to this new environment is the growth of PKI-enabled commercial Web servers with built-in access control capabilities. These features will help the department provide basic protection of the information stored on its networks, Nolte says.

Nolte believes that the next major advance in DOD PKI systems will be the extension of digital identities to software objects and other parts of the architecture. But he says the challenge is validating and identifying all of these objects. For example, the Joint Tactical Radio System (JTRS) is a software-definable radio. PKI could serve a variety of purposes for this system, such as allowing users to load software to ensure the data comes from a validated source. Warfighters using JTRS sets also may require PKI to access network-based functions. “We believe there is a large, growing need for many more device PKI services on our networks. That’s a significant piece we’re beginning to determine how to support, which may be 10 times the number of people we have on our networks. That could be a gigantic part of our PKI problem set,” he says.

Accrediting an individual’s identity is critical to issuing PKI credentials to personnel. But checking a machine’s identity creates a new set of difficulties. Nolte says that because a device cannot be asked to provide information such as a driver’s license, mechanisms must be put in place to ensure that machine names are not duplicated.

The looming question of machine and system validation will force the program to look at different ways to deliver PKI services. Nolte believes that it will be a Web service capability. However, he is not sure whether the Defense Department will provide this function or it would be better to outsource it. “We don’t know the answer yet. It could be with that volume—potentially 40 million things or devices—we ought to think of new ways to solve the delivery and support problem,” he ponders.

Web Resources

DOD Public Key Infrastructure Program Management Office: www.defenselink.mil/nii/org/sio/ia/pki

Information Assurance Support Environment: http://iase.disa.mil/index2.html

August Schell: www.augustschell.com

Comments