The NGA's Emerging Tradecraft

Threats to the United States from across the world are more frequent and persistent, from nation-state actors to terrorists to rogue players. As a result, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, a combat support agency that provides key imagery, intelligence and geospatial information to the Defense Department and to the intelligence community, has had to change some aspects of its tradecraft, says Susan Kalweit, director of analysis at the agency known as the NGA.

Kalweit, who oversees worldwide about 2,200 NGA analysts and another 1,800 employees of different skill sets, spoke at AFCEA NOVA’s Intelligence Community Information Technology Day in February, in addition to speaking with SIGNAL Magazine recently.

“The situations in the world and the geopolitics are just so much more complex,” she says. “Take Syria, for example. You’ve got the Russians there; the United States is there. You’ve got Iran and Israel involved, and Iraq. The complexity of the situation is high. And our adversaries, especially near-peer adversaries, Russia, China, Iran, North Korea, they’re getting smarter. It’s a greater challenge. We’ve got to be better.”

To the director of analysis, part of the NGA’s advancement involves putting to use the agency’s abundance of data, employing artificial intelligence and strengthening the human-machine team.

“What we have now is a wealth of data that can describe human activity, just about anywhere in the world, just about 24/7,” Kalweit admits. “And because machines can look at more data, can analyze more data, and can put out many more alternatives and weigh those alternatives in many more ways than the human brain can do alone, the potential for elevating our critical thinking becomes, I don’t want to say limitless, but it elevates it to places that we as humans alone could not get to. And that bodes well for intelligence, which fundamentally relies on critical thinking as a key skill set.”

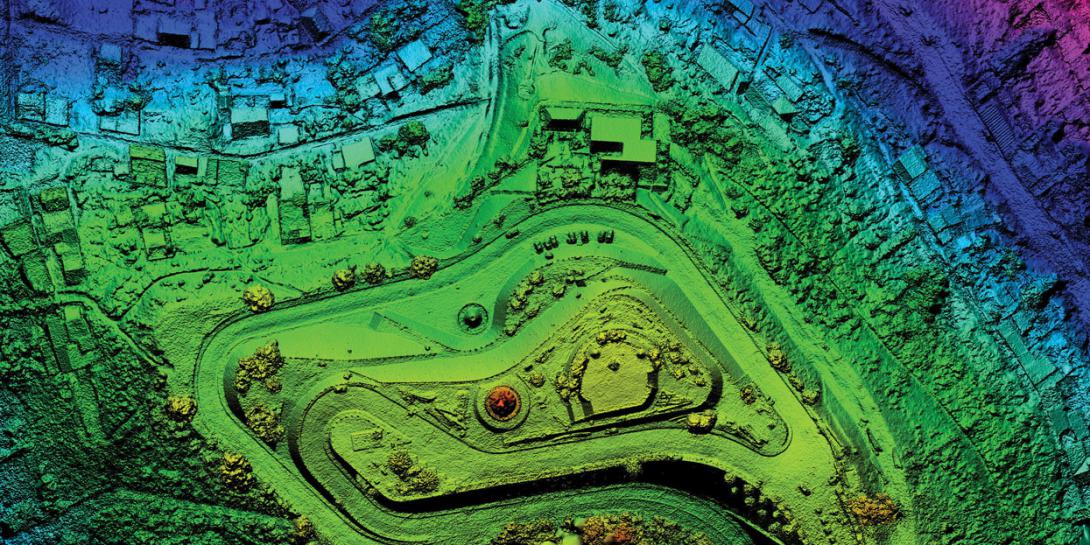

To provide geospatial intelligence about global threats, the NGA is looking at how to employ existing technologies differently, as well as harnessing emerging technologies. “We are taking a look at what technologies we do have today that we’re using in more traditional ways of working with GIS [geographic information systems] or working with imagery data, and how we can use these existing technologies in new and different ways,” she states.

Emergent technologies her department is examining include computer vision, data analytics, advanced data visualization, automation, artificial intelligence and machine learning, among other capabilities. Such technologies can help the agency adroitly understand and interpret what the vast amounts of data indicate about adversarial activities. The agency also can use the capabilities to anticipate adversarial behaviors, with greater insights in terms of the meaning of those activities. In addition, Kalweit is paying attention to technologies that contribute or free up time for humans to do other tasks.

“The change in our tradecraft, the change in the way we do our work every day truly is being driven by an increased complexity in how our adversaries behave,” she confirms. “The need is for us to get information, insights and knowledge into the hands of our customers faster. That has driven us to need to use all the data.”

And in that journey, Kalweit has become a champion of artificial intelligence at the NGA, increasing its use within the agency and throughout the intelligence community. Both the Office of the Director of National Intelligence’s Augmenting Intelligence Using Machines Center and the Defense Department’s Joint Artificial Intelligence Center are “very important” to the NGA. “We have a foot in both camps,” Kalweit stresses.

“Artificial intelligence, where it is now, but especially where it may go in the future, enables critical thinking to new levels,” she says. “It elevates our ability to do critical thinking because it augments our ability to look at many more alternatives than the human brain alone can do. And I think that’s the key part.”

In identifying where artificial intelligence and machine learning can best be applied, the director of analysis refers to a matrix that categorizes intelligence into four sectors: (1) the known-knowns; (2) the unknown location, known behaviors; (3) the known location, unknown behaviors; and (4) the most difficult, the unknown location and unknown behaviors, or the unknown-unknowns. She cites that, currently, machines are best applied to tracking the known-knowns. And given that her group spends almost 50 percent of its efforts in monitoring the known-knowns, the potential time-saving impact is great.

“When you talk about known location and known behaviors, the more data that I can throw at a machine to just stare virtually at a known location, looking for indications that known activity is changing, machines can do that a whole lot faster, easier and consistently than humans,” Kalweit notes. “And machines can analyze all that data a whole lot faster than humans can.”

Moreover, smart machines are free of the emotional, psychological or cultural baggage, which humans carry and place a bias on what the data is reporting, Kalweit adds.

Correspondingly, humans excel at creative, critical and innovative thinking. “They excel at collaborating and creating diverse teams,” she continues. “They excel at engaging with other people to solve hard problems. So whether it’s the unknown location with the known behavior or the known location, unknown behavior or the unknown unknowns, that is where we must apply critical thinking.”

And while adapting to a human-machine team dynamic will take time at the NGA, Kalweit already sees intelligence analysts being inspired and creative in taking advantage of the contribution that machines can make, especially when it applies to monitoring the known-knowns.

“In the known-knowns, where [the analysts] have seen machines help them know when an activity of interest is most likely happening and that they should look here, they have embraced that,” she notes.

She shares a recent example in which one of her teams was monitoring well over 100 locations. “That team of three could not look at all 100 locations,” she notes. “They had to sort of choose a sample [of locations] that made it certain that they were looking at a frequency that was giving them an answer. Now, they are able to have one person responsible for that same number of locations, and every location in essence can be looked at by a machine.”

And through their experience as analysts, paired with the feedback from the machine learning algorithm, they were able to trust the machine’s output after a couple of weeks, Kalweit confirms.

“Adaptation doesn’t happen overnight,” she cautions. “The human being is looking at that location and saying, ‘Yes, you’re right’ or ‘Oh, no, you’re not.’ And when the machine says, ‘I saw activity here,’ and an analyst says, ‘Oh, no, that’s not the activity,’ the machine is learning and saying, ‘Oh, okay. I’ll do better next time.’ In the meantime, as humans, we’re enabling the machine to be better, and we’re also building more confidence in the machine through that interaction. That’s how the adaptation is happening.”

She is working to take that human-machine team effectiveness and grow it across the division, connecting it with the NGA’s focus on activity-based intelligence. That tradecraft, which originated in the national counterterrorism (CT) mission, has broadened to more traditional missions in the NGA.

“Over the last several years, we’ve developed a new trade craft, if you will, in our business, that we call activity-based intelligence,” Kalweit notes. “It was born from needing to discover targets of interest for the CT mission, and lots and lots of data that were becoming available to us.’”

And as CT analysts moved into other offices that were focusing on Russia, China and Iran, “they brought with them sort of a new way of thinking about problems,” Kalweit suggests. “They proliferated this tradecraft when they moved into other areas and sat next to other analysts and said, ‘Hey, I think we could solve this problem in a new and creative way by applying what I learned over in the CT mission area.’”

And that analyst-to-analyst sharing is how her team will proliferate the new tradecraft, the use of artificial intelligence and improved human-machine teaming. “I can talk until I’m blue in the face about the advantages that computer vision is going to have on monitoring targets, [but] nothing convinces analysts more about new ways of doing things than their peers showing them examples of what has worked for them and how it can be applied in their mission,” she emphasizes.

Kalweit attests that the organization has to acknowledge the fear that humans have about computers replacing their roles. “I would offer that’s exactly what we have to deal with, which is the psychological activity that goes on in the human brain that signals fear,” she states. “It is how do we help them move from a world of fear and reaction to a place of creativity and problem solving and collaboration. [It is] creating an environment that enables folks to see opportunity, rather than disadvantage. And it’s a really, really tricky thing to do.”

The director of analysis offers that the transition starts with the specific words used. “That is the deliberate reason why I talk about the human-machine team and why humans come first, and why when I talk about the known-knowns, I say it’s mostly machine but enabled by humans,” she reasons. “So when I talk about the unknown-knowns or the known-unknowns and the unknown-unknowns, that’s a research and discovery piece, and it is mostly humans enabled by machines. In that whole dialogue, I have always included the human. I’ve also always included the machine, just in different roles.”

Once comfortable, the NGA analysts can move from the roles that computers take on to where humans excel—a much-needed change, Kalweit suggests. “What I feel bad about, is that the talent I have in my workforce, to think beyond what is known, isn’t totally used, because I have to monitor the known-knowns,” she says.

“In conducting our mission, it is imperative that we augment, automate, elevate our analysis in order to provide the decision analysis that our customers need so that they can take actions that save lives and protect the security of our nation,” Kalweit stresses. “We really owe it to our customers from the White House to our troops deployed in the field and everywhere in between to tell them everything we can know about our adversaries’ actions from a GEOINT [geospatial intelligence] perspective.”

Comments