Army Researchers Plotting Upgrades to 3-D Mapping Technology

U.S. Army researchers improved on the service’s 3-D terrain mapping system by reducing the system’s weight by 250 pounds and making the BuckEye operational from drones. Now they are developing a capability allowing the system to collect data from higher altitudes, covering a larger swath of land and considerably improving the technology’s efficacy, Michael A. Harper, director of the Warfighter Support Directorate at the U.S. Army Geospatial Center, says.

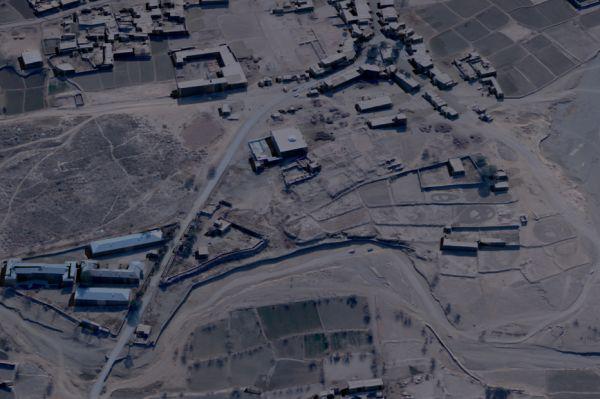

The High Resolution 3-D Terrain Data system is a multipurpose platform supporting requirements for collection of unclassified geospatial data for terrain mapping. BuckEye operates on manned and unmanned aircraft and consists of a 60-megapixel color camera working in conjunction with the Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) system to provide the high-resolution data.

“We spent some research and development dollars on trying to reduce the size and weight … Traditionally, it’s 350 pounds, but we significantly reduced it to a 100-pound payload to go into an unmanned aerial system,” Harper says, adding that troops operate two BuckEye unmanned aerial systems now in Afghanistan.

Army engineers too are working with industry to improve the capability tenfold. Currently, the BuckEye system scans and collects data from about 100 square kilometers per four-hour mission. “With BuckEye 2, which is what we refer to the prototype as, we’ll collect about 1,000 square kilometers in that same time period. By increasing the power of the laser, you can fly from a higher altitude, and when you go to a higher altitude, it improves your swath of the ground,” says Harper, who declined to name the company collaborating with Army researchers until the prototype and testing are complete sometime this fall.

The 3-D mapping capability made it into the military’s inventory in 2004, when the Army had a need for unclassified, high-resolution geospatial data for tactical missions. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in late 2010 conducted a study at the behest of the House Armed Service Committee into the lack of high-resolution, 3-D terrain data for combatant commanders all over the globe. The study validated congressional concerns and revealed that, apart from Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. military had a gap totaling 28 million square kilometers in the required HR3-D maps. The Army Geospatial Center now provides high-resolution, 3-D geospatial views of urban areas and unprecedented awareness in urban environments, Harper says. The Army uses commercial, off-the-shelf sensors to accomplish its missions. The camera is manufactured by U.S.-based KEYW, and Canadian-based Optech manufactures LIDAR.

Operators first mounted the system in helicopters and then migrated them in 2005 to fixed-wing aircraft. The technology deployed to Iraq in late 2004, where the Army collected and mapped data for more than 85,000 square kilometers. “We did all the major urban areas in Iraq, as well as all the major military supply routes, and then we collected on those areas over and over again to kind of keep the information current so the soldiers would have current imagery and elevation data,” Harper explains. The missions in Iraq netted a “revolutionary data set,” which includes more than 2,000 tiles of LIDAR elevation data at 1-meter resolution and 1.8 million color images at 10- to 15-centimeter resolution, according to Army documents.

The system deployed to Afghanistan in 2006, and since then, operators have collected data on about 463,000 square kilometers, roughly two-thirds of the country. In January 2012, BuckEye deployed a fixed-wing system to Africa to support the geospatial needs of U.S. Africa Command.

Repeated missions over the same areas means troops have access to the most up-to-date imagery, which can differ from one season to the next with changes in foliage or river levels, as examples, or following urban construction projects, Harper says. The collected data is pushed to the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency for dissemination and sent to units wherever needed.

“Traditionally, when the Army plans operations, it’s at a 1-to-250,000 scale, or a very small map scale, then we execute it at a 1-to-50,000, or tactical map scale,” Harper explains. “If you look at the types of operations that we’ve done in Iraq and Afghanistan, they are really planned at the tactical scale and executed at the urban scale or even that human scale. It adds to [troops’] safety and security. With your higher fidelity data, you can conduct more precise operations, you can reduce casualties and collateral damage.”

The Army’s eight systems have been deployed primarily for tactical missions over the years, but they also can be used to fill mapping needs for humanitarian assistance, disaster response and development, and stability operations, he adds.

And it’s not just for Army units. “The Navy special warfare group is probably one of our biggest customers. All of the data is used across the intelligence community by all the services at every echelon,” he says.

There are no plans now to increase the number of systems. “I’m not sure we need to increase the inventory, but there’s this huge requirement for the data as soldiers now, especially in the special operations community, move from Afghanistan to other contingency operations. They want they same fidelity of data that they had when they were in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

Comments