Depot Service Changes With Technology

The march of digitization has changed the mission of a longtime U.S. Army maintenance and repair depot from fixing broken radio systems in a warehouse to supporting troops using the newest software-driven communications devices in the field. This support ranges from testing or even manufacturing new gear in partnership with industry to integrating new information systems in combat zones.

The Tobyhanna Army Depot, Pennsylvania, has had to evolve with the changes in command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (C4ISR) systems in the information age. Changes in technologies and capabilities have been matched by the increasingly rapid pace of technology insertion into the force. The servicing of digital technology has expanded into new fields of operation.

Test facilities evaluate communications security, range threat testing, fire detection radars and satellite communications terminals for the Army as well as for other services. A rapid prototyping machine allows small additive manufacturing on plastics for prototyping. And, an Army language lab that can be deployed overseas helps military personnel in various countries around the world learn English so that they can train on U.S. systems and interoperate with their U.S. counterparts.

While the depot’s mission is defined as providing the overhaul, manufacturing and technology insertion services for C4ISR equipment, its activities extend into other areas that are increasing in importance in the digitized force.

“We keep the equipment going,” declares its commander, Col. Gerhard P.R. Schröter, USA.

The depot’s biggest challenge is the same one facing much of the U.S. defense community—providing the same, or greater, level of performance with fewer resources, the colonel says. In addition to embracing efficiency tools such as Lean and Six Sigma, the depot conducts a significant amount of cross training among its personnel to increase organizational agility and productivity. The depot must operate competitively in the C4ISR readiness arena, so it must vie for workload as if it were in the private sector.

“It’s how do we adjust to some of the fiscal realities—and make those adjustments internally—and ensure that we don’t limit ourselves for future development as we go off into 2020 and beyond,” he says.

This is especially important as the depot operates in the joint arena, the colonel adds. Its mission includes activities supporting U.S. Air Force and Marine Corps technologies, and those efforts are evolving to greater support in the joint environment.

Frank W. Zardecki, Tobyhanna’s deputy commander, relates that the changes in technology impelled the depot to specialize in nondevelopmental items (NDI) and commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) gear. In many cases, the depot can use commercial manuals rather than develop complex technology documentation. “We have carved out a niche in supporting NDI/COTS systems because, obviously, that is the future,” he says. “Technology is moving so rapidly that we are putting this equipment into the hands of the warfighters without going through long developmental projects, so we work very hard at being able to support those types of equipment.

“We’ve evolved into a logistics support center as opposed to a traditional depot, because we do so many things differently than we did 10 or 20 years ago,” Zardecki adds. “It’s all about the technology.”

Col. Schröter notes that as technology has become more digitized, gear has become smaller and often disposable. Tactical radios also are more reliable. With some systems, Tobyhanna focuses more on integration than repair. Elements such as cabling, harnesses and incorporation into larger systems have become prime tasks for the depot as technology evolved. “We’ve gone beyond ‘store and fix,’ to work sustainment, to manufacturing and systems integration in addition to the traditional role of repair and overhaul,” he relates.

For example, the Vietnam-era VRC-12 radio had a mean time between failures (MTBF) of about 250 hours. The Single Channel Ground and Airborne Radio System (SINCGARS) that appeared in the late 1980s offered an MTBF of more than 6,000 hours. Today’s small handheld radios tend to be more disposable than repairable.

Previously, radios used to come to the depot for repair and overhaul on a regular replacement cycle. Now, armed with reliability data, experts install sensors that report when a component might be failing. The radio can be serviced when necessary—or even just before—instead of on a constant basis.

The depot’s internal technology master plan serves as its road map for how it will exploit new technologies. It also encompasses the public-private partnerships that Tobyhanna has with nearly two dozen different companies, the colonel adds. These partnerships include traditional large defense manufacturers and service providers as well as smaller businesses. Partnerships are established via formal agreements that outline how the commercial firms will work with the depot to support new weapon systems, Zardecki explains.

The depot has many unique capabilities in areas such as light manufacturing and systems integration, he continues. Many contractors lack these capabilities, so Tobyhanna partners with them to provide key pieces of equipment for their systems. And, the depot can provide field support in fielding and sustaining those systems until they transition to full maintenance. For example, Tobyhanna has partnered with several companies to perform system integration into shelters.

“Partnering with industry also allows us to evolve and develop our skill sets,” Col. Schröter points out. “[We are] riding the wave of technology evolution as opposed to sitting on the beach and waiting for something to happen to us.”

The colonel emphasizes that this becomes particularly useful with upcoming systems. When a new system is in development and Tobyhanna can become part of the program early, then the depot can train its workforce to support that system as it becomes a reality. “We start right up front as the system is developed, and then transition over to sustainment,” he says.

At the heart of technology support is test equipment, Zardecki observes. The depot’s master plan calls for automating new text equipment while also upgrading the facility’s infrastructure to support new and emerging systems. Tobyhanna provides field support through more than 70 forward repair activities throughout the world. These field representatives used to be more hands-on-equipment experts. Now, they have to know how to address software concerns in the new software-driven radios.

And the new technologies are placing greater emphasis on field service. Col. Schröter notes that as U.S. forces entered Afghanistan and Iraq, they generated an increased requirement for support. These forces received rapid technology insertion with systems such as Blue Force Tracker and surveillance technologies. These assets needed both responsive and proactive support on site.

Even the change of vehicles mandated new equipment for integrating the advanced information technologies. Moving between Iraq and Afghanistan required new insulation kits, for example.

In some cases, the depot’s forward repair team worked on equipment in the field between deployments. Instead of waiting for gear to be removed to a base out of theater, the depot used its communications-electronics evaluation repair teams (CERTs) to conduct repairs in theater. Col. Schröter notes that the depot’s CERT personnel have reset more than 100,000 SINCGARS units and 100,000 electro-optic night vision devices in the field.

One problem that arose in Iraq affected the ALQ-144 infrared jammer, which is mounted on Army helicopters. Landings in brownout conditions would cause sand to be sucked into the jammers, rendering them inoperable. Zardecki relates that, working with the Communications-Electronics Command (CECOM), Tobyhanna experts designed filter systems and modified all the helicopters’ survivability equipment so they would operate in brownout conditions.

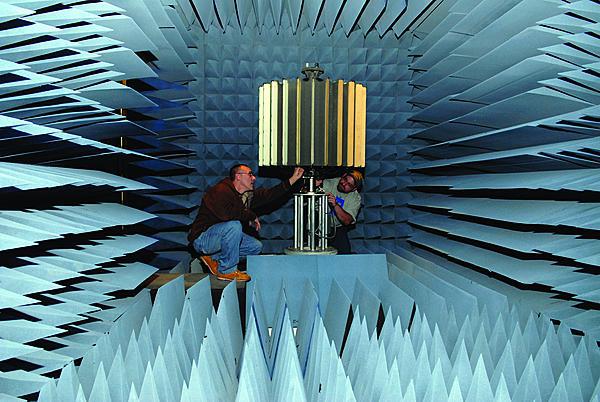

At the depot, the Firefinder counter mortar radar system is tested using unique test facilities. Even with that, Zardecki says that the test facility for the lightweight counter mortar radar (LCMR) is more distinctive. Previously, testing the LCMR would require subsequent live-fire exercises to determine accuracy. This expensive step was replaced by a live-fire test simulator developed by Tobyhanna and CECOM that entails placing an LCMR in an anechoic chamber to simulate live fire accurately. Zardecki states that this saves as much as $30,000 per system in test costs for a total of more than $20 million over the past few years.

Zardecki describes the depot’s computer-aided engineering system as state of the art. The depot can perform finite element analysis that allows experts to stress systems to ensure they will operate.

One approach that would help the depot continue to incorporate state-of-the-art test equipment involves commonality. Zardecki offers that reliable, universal test equipment that can use the same software would be high on a Tobyhanna wish list delivered to industry. Commonality would obviate the need for investing in specialized equipment with each new technology.

“We have 14,000 different pieces of test equipment,” Zardecki reports. “We’d like to downsize that and have universal equipment that makes us more efficient.” Col. Schröter emphasizes that need for access to technical documentation, training, specialized test equipment and software.

Comments