Bullet-Shredding Metal Foam Poised for Market

Scientists at North Carolina State University are preparing to bring to market a lightweight composite metal foam that combines strength, thermal shielding and both ballistic and radiation protection. The light-as-aluminum and strong-as-steel foam can be used to build body armor, artificial knees, planes, trains, trucks, space shuttles and lunar stations.

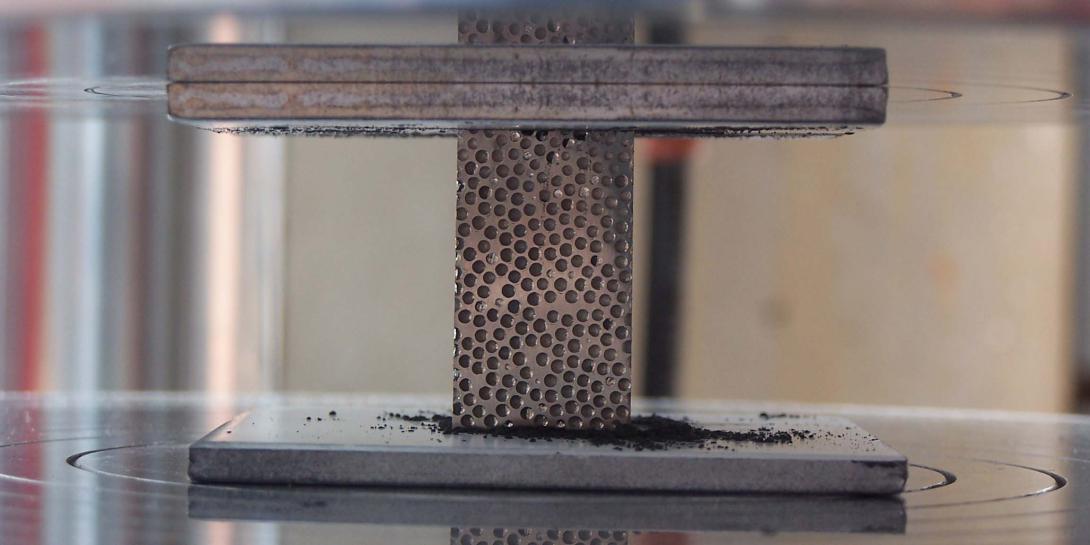

Metallic foams are man-made, porous metal materials that contain bubbles. The bubbles can be created in a variety of ways, such as by injecting air or gas, or by adding foaming agents. The process is similar to adding baking soda to a cake to make it “fluffy,” explains Afsaneh Rabiei, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at North Carolina State University and the innovator behind the composite metal foam.

Most metal foams have uneven cell structures, but Rabiei’s technology uses uniform spheres surrounded by a matrix. The spheres offer “cushionability” and “porosity,” she says, whereas the matrix provides the load-bearing strength and bonds the spheres together. “The problem with other foams is that the structure is very uncontrolled, and as a result, they can deform randomly, and the large porosity can buckle under loading. That’s where my kind of metal foam comes into the picture, with controlled spherical structure and added matrix between porosities to increase strength,” Rabiei says.

Experiments conducted at North Carolina State indicate that maintaining the ratio between the diameter of the spheres and the thickness of the matrix walls retains the material’s best qualities. “We questioned whether changing the sphere size from 2 millimeters to 4 millimeters or to 6 millimeters would impact the radiation shielding or the mechanical performance of the material. The answer is no. As long as we keep that wall thickness to sphere diameter constant, the properties stay more or less the same. If you change the wall thickness, that is a different scenario, and you may experience different properties,” she offers.

Rabiei’s research, which has been partially funded by the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy and the Defense Department’s Joint Aircraft Survivability Program, first gained widespread attention in 2008, when the National Science Foundation announced the creation of the world’s strongest metal foam. At the time, Rabiei envisioned the material being used primarily for high-impact protection: car bumpers and armor plating, for example.

During testing, the metal foam obliterated bullets fired at close range. Furthermore, a 28 mph crash using a car bumper made of Rabiei’s composite metal foam would equal a 5 mph fender bender, according to a video provided by the National Science Foundation.

“The ballistic and blast resistance of the material is important because it can absorb the impact energy and dissipate it. When you put it in any structure, from vehicle armor to aircraft armor to body armor, it can offer good blast and ballistic performance with light weight,” Rabiei emphasizes.

More recently, North Carolina State University informed the world that Rabiei had tweaked the formula so that the foam now shields against radiation much more effectively than traditional solutions, making it suitable for nuclear protection and even for space applications. “There is a lot of potential for space—for example, the lunar stations—because it can protect against all sorts of radiation. The application can be for space stations, for shuttles, as well as for nuclear tasks, such as the transportation of nuclear waste materials,” the professor elaborates.

For example, she says, a super-strong container could hold the radiation while protecting the cargo in case of a crash or train derailment. “Just to protect against puncture or the leakage of nuclear material is huge,” she says.

Rabiei and her team added tungsten, steel and vanadium, so-called “high-Z materials” that effectively block radiation. The researchers tested shielding performance against X-rays, neutron radiation and several types of gamma rays. They found that the high-Z foam is comparable to bulk materials at blocking high-energy gamma rays and much better than bulk materials—even steel—at blocking low-energy gamma rays. Similarly, the high-Z foam outperformed other solutions at blocking neutron radiation and performed better than most at blocking X-rays.

“Even though tungsten and vanadium are heavy materials, we could accomplish better radiation shielding in all three categories of gamma ray, neutron and X-ray, and at the same time, mechanical properties did not deteriorate, and we can maintain the low density. This is important because we did use some heavy materials like tungsten, and we can still make something as light as aluminum and also maintain the mechanical properties,” Rabiei adds.

For now, the composite metal foam is not quite as effective as lead, but that likely will change soon. The testing done so far was preliminary, and the material was not yet optimized for peak performance. “In order to take it to a point where it is exceeding the performance of lead, we need to add more of the high-Z elements and optimize the performance of each element to where it is perfect. We just added a little bit, and it worked very well. How much would be enough is what we need to determine from this point on,” Rabiei reports.

Although the high-Z materials are heavy, researchers may be able to add more without significantly increasing the composite metal foam’s weight. “With the amount we added, we couldn’t see any downside. Adding more could be increasing the density to some extent, but that has to be explored further,” she says.

And now the material is about ready to transfer from the lab. “It’s pretty much to the point where we can start commercialization. We’re now talking about potential fundraising and making it available for the nation. There has been more than $1 million worth of research done from where it was an idea to now, and it is time for us to start taking it out to taxpayers to benefit from it,” she says.

In fact, the team is working on a commercialization plan. “It is not coming in the far future. It is coming soon,” she promises.

Although the military, NASA and others have shown interest, the major remaining challenge may be finding someone willing to put the material to use. “We are human, and every time something new comes up, people resist coming out of their comfort zones to give it a shot,” Rabiei states. She indicates that she looks forward to finding one person creative enough to put the new material in a structure and demonstrate its benefits to the world.

To illustrate her point, Rabiei recalls that her own passion for metallurgy was ignited when she was still in high school, visited a factory and witnessed the power of forging red-hot metal. At 19, she authored a 600-page book. She went from one publisher to the next, but they all seemed to want more experienced authors with “multiple degrees hanging on their walls,” she says.

Finally, an older gentleman contacted her with an offer to publish the book. “He told my parents many years later that he still had bread on the table because of that book. God bless his soul,” Rabiei says. “Somebody has to be courageous enough to step forward and trust.”

Comment

Balistic Protection / Body Armor

Stumbled across your article looking at a visit to NC state with my son.

Curious about the Bullet-Shredding Metal Foam. I work for the department fo the Navy and see the potential for use in our firing ranges where we use AR500 plate - 3/8" and 1/2". Also see the potential use for body armor for special warfare teams where weight is big factor.

How does it compare to AR500 plate? What ballistics has it been tested against? Can we get a piece of the foam plate for testing comparisons? Would share the data with you.

Bernie

It would be interesting to

It would be interesting to make DU metal foam for tank armor.

Comments