U.S. Army Prototypes to Ease Warfighters’ Reliance on GPS

U.S. Army engineers developed technology prototypes aimed at weaning U.S. forces from dependence on GPS systems.

The U.S. military’s increased reliance on global positioning satellite (GPS) technologies has triggered adversarial forces to improve upon technology to disrupt the warfighters’ usage in the age-old war games of one-upmanship.

U.S. Army engineers developed technology prototypes aimed at weaning U.S. forces from reliance on GPS systems. The Warfighter Integrated Navigation System (WINS), while intended to serve as a backup to GPS usage, not as a replacement, can operate independently and free of a satellite link and still give warfighters precise positioning and timing data.

It would augment the Army’s Rifleman Radio system, a lightweight, rugged, handheld radio that transmits voice and data via the Soldier Radio Waveform. In essence, the Rifleman Radio acts as its own router and network backbone provided by the Warfighter Information Network-Tactical to transmit information.

But it’s inherently vulnerable.

“The source for Rifleman Radio is commercial, and that’s what we’re trying to protect,” says John Del Colliano, position, navigation and timing branch chief at the Army’s Communications-Electronics Research, Development and Engineering Center (CERDEC). “We’re seeing more and more evidence that there will be threats brought against GPS usage, primarily because, I think, we’re seeing more and more evidence that our reliance on GPS is so high. It makes sense that that’s what the enemy would pick on.”

Engineers at the CERDEC laboratory at Aberdeen Proving Ground (APG) in Maryland churned out the prototype to “allow us to investigate what technologies we can use to essentially become GPS free,” Del Colliano adds. “But it also is to make the GPS more robust. We want to do both things; make it harder for you to take it away from me, but if it does get taken away, what else can I do in its place?”

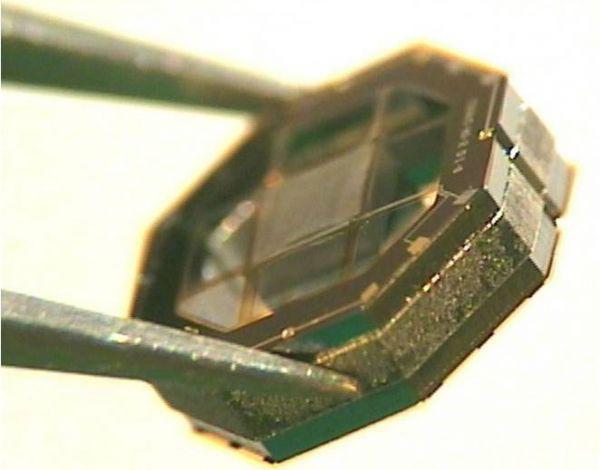

The systems are part of CERDEC’s disruptive technology in fielding position, navigation and timing (PNT) program advancements. The Army also is manufacturing the microchip-sized prototype Chip Scale Atomic Clock (CSAC) to provide highly accurate location and battlefield situational awareness in the absence of GPS capability. The CSAC can give dismounted soldiers atomic clock capabilities in an ultra lightweight capacity.

“An atomic clock, which is recognized for its accuracy, is used by the military in larger systems,” Del Colliano says. “However, the typical atomic clock is large, heavy and requires lots of power. Large systems/platforms like bombers have the advantage of having more power and space to accommodate a full-scale atomic clock, but that’s not true for a soldier on the battlefield or for munitions being fired.”

The tiny CSAC, at 15 cubic centimeters, can provide precise time to a GPS receiver if jammed or spoofed, a term used when false GPS signals fool receivers.

Through the Defense Department’s Manufacturing Technology (ManTech) Program, created in 1956 in response to the nation’s growing need for advanced production processes that focused on defense essential needs beyond normal industry risk, CERDEC was able to lower the cost—from $1,500 to $3,000 per unit to $300, Del Colliano says.

“The big thrust here is projecting forward into the future where we could be operating, where we may want to operate and where you may not be able to rely on GPS,” says John Willison, director of CERDEC’s Command, Power and Integration (CP&I) Directorate. “The Army and [Defense Department] has been heavily reliant on GPS for positioning and for timing … so two radios, two communications pieces of equipment, two computers on the network—anything that requires an authentic and precise source of timing data typically relies on commercial GPS.

“There is a recognized threat out there that that may be denied, depending on where we’re going. And we may want to operate in places where [GPS] is not available. … Inside of buildings, underground, in caves, whatever. And so we’re looking at all kinds of technology that would allow you to still have the ability to get precise source of time and also the ability to know where you’re at, no matter where you’re at.”

A 100,000-square-foot APG facility lets engineers and scientists fabricate and rapidly push out prototypes in small quantities, be they for testing purposes alone, or for fielding in small numbers to Special Forces, for example, Willison says.

As long as GPS systems are operational and trustworthy, troops will rely on them for primary positioning and timing data, Del Colliano says. A pitfall of the WINS system, being developed both for dismounted and mounted use, is that it loses accuracy the longer it operates offline from a satellite linkup. It’s intended to work seamlessly with GPS systems to provide soldiers with a backup should GPS be denied, and a method to verify that a GPS connection has not been spoofed.

Comments