Communications Top Defense Technology Wish List

A U.S. military that has dropped its guard on advanced technology development must now steel itself to catch up to and overtake peer rivals that have capitalized on U.S. complacency to surge ahead in defense research and development. Taking back the initiative and restoring U.S. military supremacy will require rapid advances in space-based lasers, cyber countermeasures and hypersonic attack vehicles. And linking these systems will require communications capabilities that establish and maintain spectrum dominance.

Michael Griffin, U.S. undersecretary of defense for research and engineering, is working to fulfill the new National Defense Strategy that Defense Secretary James Mattis released in January. Griffin took charge of the new position of undersecretary of defense for research and engineering one month later. His priorities are based on that overall strategy, but the details are still being worked out. “We know we need to make change—and we’re going to do that—but we’re at the early stages,” he says.

Many of the technology targets on the radar for Griffin’s office arise from advances made by near-peer and peer adversaries. As with many other top U.S. defense officials, Griffin points out that for 15 years the military focused its technology lens on defeating terrorism in asymmetrical operations while neglecting to explore new military capabilities that could be applied across the broad spectrum of combat operations. U.S. adversaries used that period of technological inactivity to pursue their own research thrusts, which has helped them close what had been a large gap favoring U.S. military capabilities. Now, the United States must reignite its technology fuse or risk losing its spark to adversaries.

“It’s really been quite a while since the United States has had to rethink its defense strategy,” Griffin declares. The last updated National Defense Strategy was published 10 years ago, when George W. Bush was president.

But Griffin offers that U.S. technology complacency predates the war on terrorism. “We have really not modernized the way we fight wars since the Reagan era,” he states. “By the end of that era, the ball had come down during President George H.W. Bush’s term: The Soviet Union broke up, China was not then on the ascendancy, and we did not have a pressing need to modernize.” The modernization wave of the 1980s, when U.S. forces added stealth aircraft, GPS capabilities and advanced precision-guided munitions, introduced a revolutionary set of technologies that began a period of “utter dominance,” Griffin notes.

However, these once-revolutionary technologies are about 40 years old, and adversaries have developed their own versions of them. To retain military dominance will require new approaches for the U.S. military, Griffin emphasizes.

Topping the list of technology targets for strengthening the U.S. military are more resilient communications that work across the joint force, he declares. This is the linchpin of all the proposed technology advances, and it includes all domains: land, air, sea and space, Griffin states. “Nothing that we do, whether in peace or war, works well without guaranteed communications,” he says.

Griffin explains that how the Defense Department will re-architect the communications strategy remains to be determined. Because the department uses commercial capabilities for about 80 percent of its communications, the private sector will play a large role in the results of this re-architecture. “As it takes shape, you can guarantee that commercial capabilities will be a major part of it,” he says.

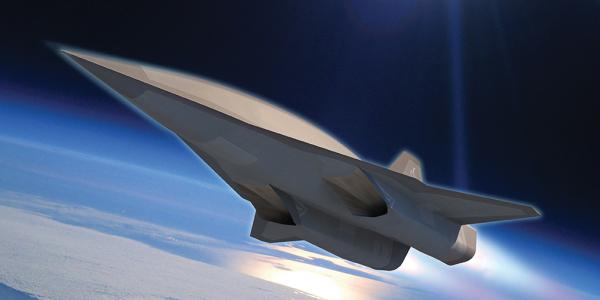

The undersecretary also places hypersonics high on his list of necessary capabilities, and he includes both offensive and defensive applications. China has made great strides in hypersonics, which the United States pioneered but opted not to weaponize. Both Russia and China have weaponized hypersonics, so U.S. officials must rethink that earlier decision, Griffin declares. The military must develop offensive hypersonic systems that can counter an enemy’s capabilities, and it must develop defensive systems that can protect U.S. assets.

Another area of need involves directed energy weapons. “They’ve been the weapons of the future for a long time. It’s my goal to make them weapons of the present,” Griffin declares.

He continues that U.S. ships, planes and forward operating bases must be able to defend against swarming attacks, and this cannot be realistically done without directed energy as part of the defensive posture. Directed energy weaponry also is necessary to achieve “truly dominant missile defense,” Griffin offers, and that must be space-based. Directed energy weapons in orbit will be essential for shooting down ballistic missiles during their boost phase. “That’s the high-leverage play in the game,” he states.

Today’s U.S. missile defense system is highly effective against limited threats from opponents such as North Korea or Iran, Griffin continues. It was not designed to counter a mass strategic missile capability. That will require developing and deploying directed energy weapons in space.

Then there is the threat from cyberspace. China has specialized in exfiltrating data, especially from U.S. government sources such as the Office of Personnel Management. Russian malware continues to infiltrate U.S. systems and interfere with others. Earlier this year, the FBI urged people around the world to reset their routers to stop the spread of Russia-linked malware. And, Griffin relates, Russians came within “a gnat’s eyelash” of disabling shipping company Maersk Line in a cyber attack about a year ago.

“I don’t even have to get into classified issues to point out that we are under constant cyber threat,” he adds. “We are going to have to learn how to counter that threat and then deal in return. We need to be able to hold our adversaries hostage in this arena, and we’re not doing that at present.”

One emerging threat that must be addressed involves swarming drones. Griffin relates that “way too many” drone incursions are taking place over U.S. military and national security properties both domestically and internationally. “That can’t be tolerated. Drones are cheap; enemies can afford to buy a lot of them. We can’t be countering drone attacks by firing Patriot missiles at them; we need to be able to handle high-volume drone raids.

“I don’t know how to do that without directed energy systems, but I also don’t know how to do that without artificial intelligence to help with the targeting and fire control,” he continues. “It just gets out of hand for conventional systems that can become saturated.”

This is just one military application for artificial intelligence (AI), Griffin observes. Intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) data is amassed in huge amounts, and the military largely uses humans to process it, he notes. The Defense Department must be able to deploy more advanced methods of incorporating AI to extract vital information from this data.

ISR needs other improvements. “The United States has exquisite surveillance capabilities,” Griffin says. “We do not have continuous, persistent, global low-latency surveillance. We do not know what is going on everywhere in the world, all the time. In today’s threat environment and the threat environment we can envision right around the corner, we have to have that.”

The annual defense authorization bill signed into law in August called for examining a space surveillance layer for missile defense, he notes. But missile defense is only one element of the need for persistent ISR. The United States needs to know where mobile missile launchers are right now, not where they were last week, Griffin points out. Development of a persistent ISR capability also will be innovative for the U.S. military.

A former NASA administrator, Griffin declares that he strongly favors the creation of a U.S. Space Force. He says he hopes Congress approves the president’s directive, although he appreciates that there will be “some breakage of china.” Nonetheless, the benefits of coalescing the department’s efforts in space will outweigh the difficulties, Griffin offers. The department has many programs that are touched by space, and they will continue, he says.

Additionally, quantum sciences—not just quantum computing, secure communication or key distribution—are important across the board, Griffin says. “We have people who are within just a few years of being able to produce quantum clocks that are a thousand times more accurate than any clock we can make,” he predicts. “That has implications for communications, communications standards, precision navigation/timing, the ability to do high-rate encrypted communications—all are enabled by quantum clocks.”

And this affects the challenge of fighting in a denied environment. If an enemy prevents U.S. forces from using GPS, then having better clocks and quantum sensors for inertial navigation would allow those forces to continue to fight in that denied environment, Griffin points out.

Industry and academia will be a factor in developing all these new capabilities, but he admits that their roles are not yet determined. “This is a new undersecretariat,” Griffin points out. While both sectors have long-standing relationships with the Defense Department, Congress has elevated the role of research and engineering with the creation of this undersecretariat. His office will be rethinking how it engages industry and academia, the undersecretary explains.

And the undersecretariat, as well as the department as a whole, is receiving unprecedented support from Congress and the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Griffin offers. “Right now, it’s full speed ahead,” he declares. “We’re working the accelerator, and we’re working the steering wheel. We’re not working the brake.”

Comments