The European Commission Plans for Second Horizon Europe

The European Union’s (EU’s) executive branch, the European Commission, is plotting a new $206 billion technology effort to draw in sophisticated artificial intelligence, quantum computing, satellite communications, industrial decarbonization, biotechnology, cybersecurity, defense, space and other technologies that will benefit the EU.

Building on the first venture of the so-called Horizon Europe effort, the second phase of Europe’s flagship research and innovation program will be twice as big as the current 2021-2027 campaign, and will be “simpler, faster and more impactful,” leaders claim.

“As part of the next long-term EU budget 2028-2034, the Commission is proposing to double the budget of the research and innovation framework programme to €175 billion,” indicated a recent commission statement. “The new Horizon Europe will boost Europe’s competitiveness and fund solutions to real-world challenges, from AI that supports doctors, to satellites that protect farmers, to cleaner, smarter ways to move, live, and work.”

In addition to increasing the continent’s productivity and competitiveness, the program aims to improve the well-being of millions of people across the continent. The program’s collaborative research efforts will also address societal challenges like disinformation and climate change.

“This commission is determined to make Europe the best place for research and innovation and for technology companies,” said Ekaterina Zaharieva, the European commissioner for startups, research and innovation in a September 15 presentation. “This is key for our competitiveness. We have proposed doubling Horizon Europe, and we presented plans to make Europe the home of startups, scaleups and life sciences.”

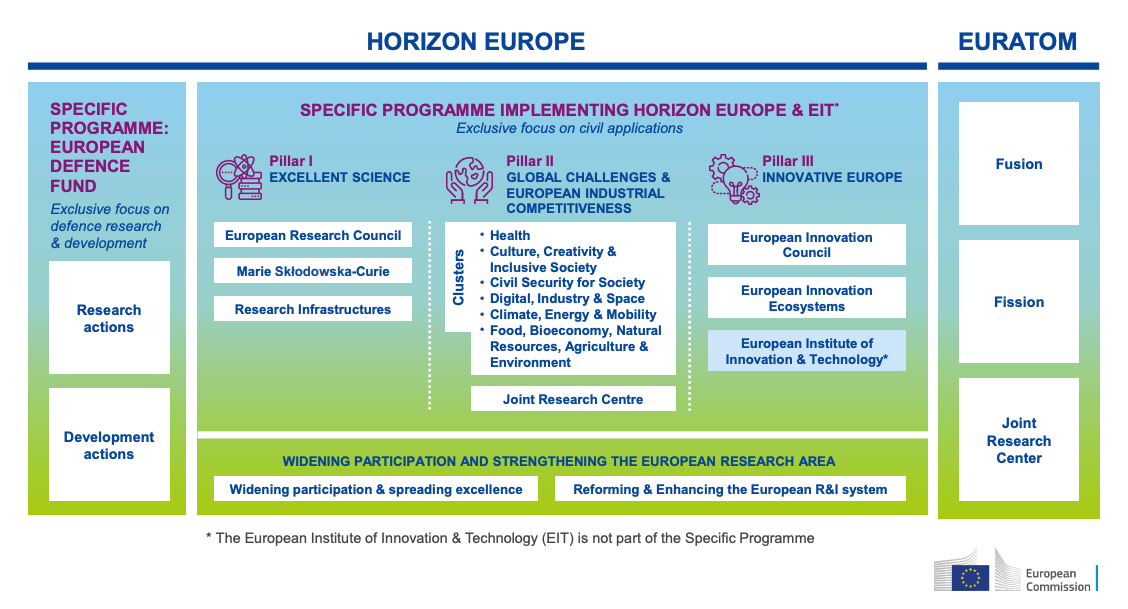

In the proposal, about €76 billion will go to improving the EU’s competitiveness and society, €44 billion to “excellent” research science through the European Research Council, €39 billion to innovation, under the European Innovation Council and various technology ecosystems, and €16 billion in European policy research and technology infrastructures, among other measures. The ventures also leverage co-funding through EU member countries.

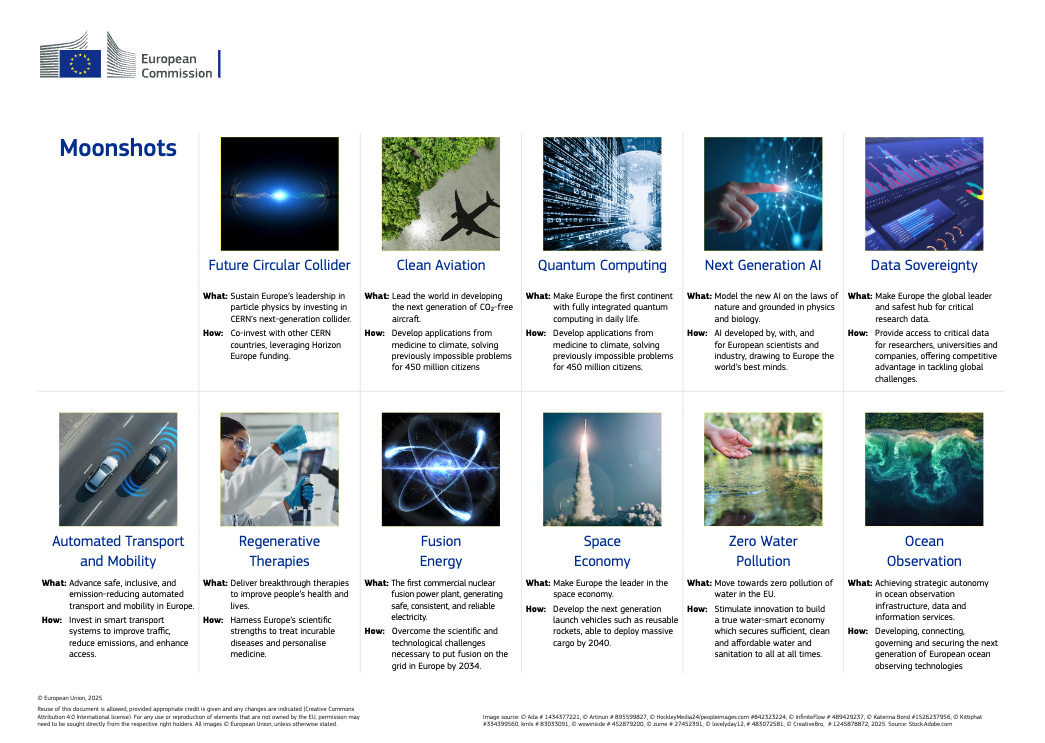

In particular, “Moonshot” objectives—ambitious technological advancements—are wanted in the following: clean aviation, a next-generation particle physics collider, quantum computing, next-generation AI, data sovereignty, automated transport and mobility, regenerative therapies, fusion energy, the space economy, zero water pollution and ocean observation, a commission report indicated.

The goals are lofty. For the circular collider, the commission wants to continue Europe’s lead in particle physics and help build the European Organization for Nuclear Research’s (CERN’s) future collider with co-investors. For clean aviation, the idea is to develop aircraft that do not emit carbon dioxide.

And for quantum computing, the commission wants to make Europe the first continent to harness “fully integrated quantum computing in everyday life.” They also want to position Europe as the “global leader and safest hub” for critical research data—to offer a competitive advantage to researchers, universities and companies that are tackling global challenges.

Next-generation AI development would be grounded in the laws of physics and biology, and the work would attract the world’s best scientists and industry to Europe, according to the commission. For autonomous vehicles, the Horizon Project aims to advance “safe, inclusive and emission-reducing automated transport and mobility” for the continent. Already active in the satellite communications market, Europe should also be the leader of the space economy, with goals of developing next-generation launch vehicles and reusable rockets, “to deploy massive cargo by 2040.”

Zaharieva sees Horizon Europe as one of Europe’s strongest brands—one that is placing research and innovation at the heart of the EU economy and its investment strategy.

“I recently heard about a team of U.S. scientists investigating a major crop disease,” she said. “They suffered severe budget cuts and many lost their positions. One professor said, ‘I really fear for the future of science.’ Sad words to hear from a scientist, because there is no future without science. In Europe, however, the future of science and innovation is one of hope, not fear.”

The program aims to attract and retain scientific talent through the related Choose Europe effort that is working to de-risk and mobilize private research, startups and innovative financing.

At the same time, the European Commission is developing “responsible AI” policy, called the European Strategy for Artificial Intelligence in Science. After a period of public comment, the organization held an eight-week call for evidence this past summer from academia, research institutions, companies, government and the public.

- Officials have outlined several AI-related focus areas, including:

- Improving access to infrastructures for researchers and innovators, including cutting-edge AI applications, large language models and high-performance computing infrastructure.

- Strengthening the European Data ecosystem, including the development of a data governance framework.

- Promoting interdisciplinary partnerships in the field of AI-supported science.

- Improving AI skills of researchers from all fields with the development of qualification and training programs to advance the use of AI in science.

- Retaining and attracting scientific talent in Europe in AI.

- Increasing coordination between the EU and member states on the use of AI in science.

- Ensuring that Europe’s distinctive approach to AI helps to set global standards and position the EU as a key actor in science and AI applications.

The European Commission’s AI strategy is expected to come out later this year, Zaharieva noted.

“Our goal is to make sure AI supports scientists and inspires innovators,” she stated. “With input from across Europe and beyond, we can now get to work on developing our AI in Science Strategy—and take a step closer towards achieving that target.”

Horizon Europe drives breakthroughs at a scale nobody can achieve alone.

Additionally, the European Commission began talks with ally Australia in September to explore a possible association agreement with Horizon Europe, holding technical discussions that could lay the foundation for potential development negotiations. The EU has had a history of collaborating with the country, based on a 1994 cooperation agreement on science and technology that continues to set bilateral research collaboration priorities.

“The Exploratory talks will focus on Australia’s possible association to Pillar II of Horizon Europe—which includes research collaboration on key priorities such as industry, digital and space to enhance industrial competitiveness, renewables energy to promote the transition to net zero and health for the wellbeing of our citizens,” the European Commission stated in a September 10 release.

The association agreement would enable Australian researchers to receive funding directly from the program and lead projects. Australia would also contribute financially to the Horizon Europe effort.

Already, more than 20 countries have an association agreement with Horizon Europe, including Canada, Korea, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and Ukraine. The United States does not have such an agreement.

“Horizon Europe drives breakthroughs at a scale nobody can achieve alone,” Zaharieva stated. “[The] Association would enable Australia to take part directly in that effort and contribute its scientific excellence to global challenges.”

The organization claims that each euro invested in the Horizon Europe program will generate up to €11 in gross domestic product gains through 2045.

The first phase of Horizon Europe featured more than 15,000 projects (as of January 31, 2025) with €43 billion of funding. Given the global COVID-19 outbreak, the organization adapted and funded pandemic-related research and capabilities.

Other program areas of note in the first phase included smart networks and services; high-performance computing; key digital technologies; next-generation internet; AI; data; robotics; photonics; Earth observation and other space technologies; “Made in Europe” efforts and a cross-platform called the European Open Science Cloud.

For example, Horizon Europe provided funds toward the EU’s new Space Programme, which includes the existing European Global Navigation Satellite System (EGNSS), the Copernicus constellation, space situational awareness capabilities and secured government satellite communications, or GOVSATCOM. The funds also aim to develop Cassini, a space entrepreneurship ecosystem, and cross-cutting space technologies that support in-orbit validation and demonstration services, space science and missions.

“[We will] continue to support the evolution of space and ground infrastructures for the two EU flagship constellations Galileo and Copernicus, and foster the evolution of EGNSS and Copernicus services,” the commission stated in its 2025 Rolling Plan. “[We will] contribute to the development of innovative downstream applications, including by combining EGNSS and Copernicus services with other services, and develop innovative space capabilities for space situational awareness, GOVSATCOM and pave the way for quantum technologies in EU space infrastructure.”

For the 2028-2034 Horizon Europe effort, leaders are now conducting interinstitutional negotiations with the European Parliament, Council and the whole Commission, about the program’s planned budget allocations.

“Our mission is clear: to prepare a bright future for science and innovation,” Zaharieva stated. “With that in mind, we will enshrine scientific freedom into European law. We will improve research careers, and we will tackle the persistent obstacles faced by women in science.”

Comments